The mounting battle between Uber, the popular app-based car service, and the incumbent taxi industry has featured court dates in Toronto, undercover sting operations in Ottawa, and a marketing campaign designed to stoke fear among potential Uber customers. As Uber enters a growing number of Canadian cities, the ensuing regulatory fight is typically pitched as a contest between a popular, disruptive online service and a staid taxi industry intent on keeping new competitors out of the market.

My weekly technology law column (Toronto Star version, homepage version) notes that if the issue was only a question of choosing between a longstanding regulated industry and a disruptive technology, the outcome would not be in doubt. The popularity of a convenient, well-priced alternative, when contrasted with frustration over a regulated market that artificially limits competition to maintain pricing, is unsurprisingly going to generate enormous public support and will not be regulated out of existence.

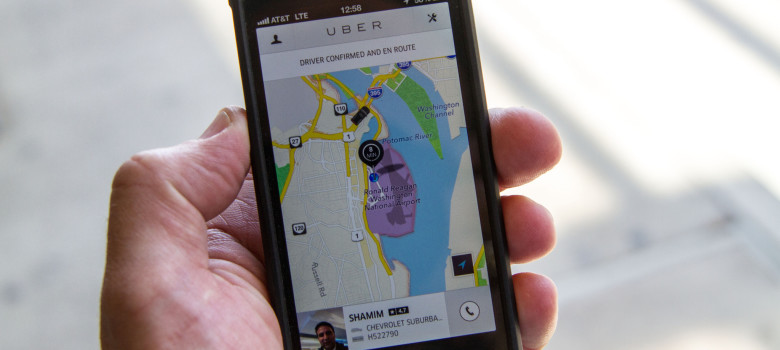

While the Uber regulatory battles have focused on whether it constitutes a taxi service subject to local rules, last week a new concern attracted attention: privacy. Regardless of whether it is a taxi service or a technological intermediary, it is clear that Uber collects an enormous amount of sensitive, geo-locational information about its users. In addition to payment data, the company accumulates a record of where its customers travel, how long they stay at their destinations, and even where they are located in real-time when using the Uber service.

Reports indicate that the company has coined the term “God View” for its ability to track user movements. The God View enables it to simultaneously view all Uber cars and all customers waiting for a ride in an entire city. When those mesh – the Uber customer enters an Uber car – they company can track movements along city streets. Uber says that use of the information is strictly limited, yet it would appear that company executives have accessed the data to develop portfolios on some of its users.

In fact, Uber blogged in 2012 about “Rides of Glory”, which it characterized as “anyone who took a ride between 10pm and 4am on a Friday or Saturday night, and then took a second ride from within 1/10th of a mile of the previous nights’ drop-off point 4-6 hours later.” The blog posting identified which cities had the largest number of such rides.

Canadian Uber users can be forgiven for wondering whether the company takes their privacy rights seriously since it does not even have a Canada-specific privacy policy. The Uber website features three privacy policies: one for the United States, one for South Korea, and a global catch-all policy for users in 48 other countries. That approach effectively lumps Canadians into a privacy policy shared by users everywhere from Beirut to Beijing to Bogota.

The policy identifies certain privacy rights (and seeks to bring global users under a European Union privacy umbrella), but does nothing to ensure that it is fully compliant with Canadian privacy law standards. Interestingly, the company does have a Canada-specific user agreement, so the company’s legal rights are designed to comply with Canadian law.

Geo-location privacy is frequently invoked within the context of online marketing, with some concerned about the prospect of being “followed” as they walk down a city street, receiving coupons or real-time offers from nearby stores. Yet the Uber situation provides an important reminder that geo-locational privacy issues extend far beyond just marketing as they allow for tracking and inferences about user behaviour that is not otherwise publicly available.

Providing locational information is a trade-off that many are prepared to make, particularly if backed by privacy rules that safeguard misuse and provide some measure of oversight. In the case of Uber, the failure to develop Canada-specific protections raises serious questions about whether the company sees itself as outside the scope of more than just local taxi regulations.

Uber has a host of issues it needs to resolve in Canada generally and Toronto specifically that include but extend well past privacy concerns before it becomes widely accepted.

For example, a friend was in an Uber car when it was involved in an accident where she was hurt. The driver did not have the right kind of insurance and now my friend is scrambling to figure out what legal remedies she may have. Another acquaintance stopped using Uber when a driver pulled over to get something at a convenience store along the way. Neither will use Uber again.

But even if the ride is uneventful, the privacy concerns are well-founded – especially if Uber is using the information in a way that runs contrary to Canadian law. This goes well beyond whether or not it’s a disruptive service and strikes at the heart of what doing business in Canada – or any country, for that matter – requires.

Some form of regulatory structure is needed so that Uber is held to account.

I think major changes are need to the system but i don’t know if the cabbies would be willing to make the changes needed for exzample in Ottawa there is 5 taxi companys but one main company owns all of them.

Then you have the issue with fares they want a 7% increase then we have the matter of the value of plates what i would like to see is set the value of plates at $50,000 and give the cabbies a 10% increase in fares but have a 10 year freeze on anymore increases.

How is this different from the geo-location information that Google collects?

Pingback: Michael Geist – Uber’s privacy problem « Quotulatiousness

Pingback: Batch Geonews: The Book of OSM, Geomancer, SPOT 7 Satellite, Tracking Poop, and much more - Slashgeo.org