The misuse of Canada’s new copyright notice-and-notice system has attracted considerable media and political attention over the past week. With revelations that some rights holders are requiring Internet providers to send notifications that misstate the law in an effort to extract payments based on unproven infringement allegations, the government has acknowledged that the notices are misleading and promised to contact providers and rights holders to stop the practice.

While the launch of the copyright system has proven to be an embarrassment for Industry Minister James Moore, my weekly technology law column (Toronto Star version, homepage version) notes that many Canadians are still left wondering whether the law applies to Internet video streaming, which has emerged as the most popular way to access online video.

In recent years, the use of BitTorrent and similar technologies to engage in unauthorized copying has not disappeared, but network usage indicates its importance is rapidly diminishing. Waterloo-based Sandvine recently reported the BitTorrent now comprises only five per cent of Internet traffic during peak periods in North America (file sharing as a whole takes up seven per cent). That represents a massive decline since 2008, when file sharing constituted nearly one-third of all peak period network traffic.

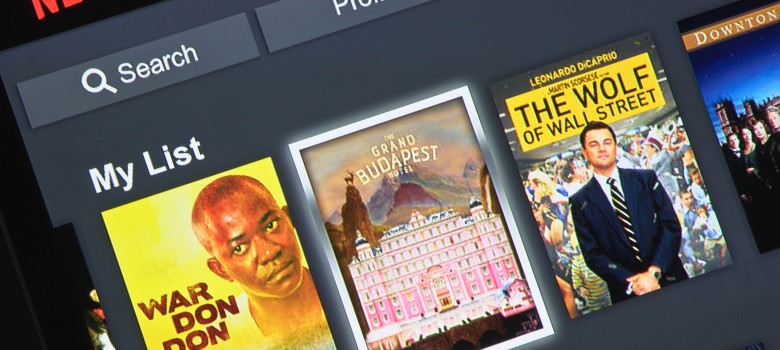

The decline largely reflects a shift toward streaming video, which is now the dominant use of network traffic. Netflix alone comprises almost 35 per cent of download network traffic in North America during peak periods with the other top sources of online streaming video – YouTube, Facebook, Amazon Prime, and Hulu – pushing the total to nearly 60 per cent.

The emergence of streaming video raises some interesting legal questions, particularly for users wondering whether the notice-and-notice system might apply to their streaming habits. The answer is complicated by the myriad of online video sources that raise different issues.

The most important sources are the authorized online video services operating in Canada such as Netflix, Shomi, CraveTV, YouTube, and streaming video that comes directly from broadcasters or content creators. These popular services, which may be subscription-based or advertiser-supported, raise few legal concerns since the streaming site has obtained permission to make the content available or made it easy for rights holders to remove it.

Closely related are authorized online video services that do not currently serve the Canadian market. These would include Hulu or Amazon Prime, along with the U.S. version of Netflix. Subscribers can often circumvent geographic blocks by using a “virtual private network” that makes it appear as if they are located in the U.S. Accessing the service may violate the terms of service, but would not result in a legal notification from the rights holder.

The most controversial sources are unauthorized streaming websites that offer free content without permission of the rights holder. Canadian copyright law is well-equipped to stop such unauthorized services if they are located in Canada since the law features provisions that can be used to shut down websites that “enable” infringement.

Those accessing the streams are unlikely to be infringing copyright, however. The law exempts temporary reproductions of copyrighted works if completed for technical reasons. Since most streaming video does not actually involve downloading a copy of the work (it merely creates a temporary copy that cannot be permanently copied), users can legitimately argue that merely watching a non-downloaded stream does not run afoul of the law.

Not only does the law give the viewer some comfort, but enforcement against individuals would in any event be exceptionally difficult. Unlike peer-to-peer downloading, in which users’ Internet addresses are publicly visible, only the online streaming site knows the address of the streaming viewer. That means that rights holders simply do not know who is watching an unauthorized stream and are therefore unable to forward notifications.

While some might see that as an invitation to stream from unauthorized sites, the data suggests that services such as Netflix constitute the overwhelming majority of online streaming activity. Should unauthorized streaming services continue to grow, however, rights holders will likely become more aggressive in targeting the sites themselves using another feature of the 2012 Canadian copyright reform package.

I’d be interested to see the actual numbers (volume) of downloads, not just the percentages. Could it be possible that overall downloads haven’t decreased at all, but are just being overshadowed by increasingly popular streaming services such as Netflix? More people are using the internet than ever before, and most of us are using it more than we did in 2008, too (for me, ~1 hr in 2008 has grown into far more hours than I’d like to admit in 2015), so it wouldn’t be surprising to me if the overall volume of downloads is increasing, even if the percentage or “share” is decreasing.

What of systems such as popcorn time which streams bittorrent files?

Popcorn Time can keep the files it downloads, so obviously that would be illegal.

But if you do not choose the option to keep downloads (it is not default), you will still probably get a letter since the rights holders would still see you’re downloading, even though they didn’t know you’re streaming.

However, it would be interesting to see it argued in court. That said, the seeding side of things would make you a distributor as well so that may complicate things.

All in all, you’re probably safer to use a streaming site if you’re going to get an unauthorized copy than to use Popcorn Time haha.

A) popcorn time has vpn functionality built into the app. (it’s subscription based but incredibly cheap)

B) seeding is turned off by default.

That must depend on the version because most versions of Popcorn time supported seeding.

Plus, the version with the “VPN” that the idiots at TorrentFreak have been promoting contains malware anyway. I’d suggest just going and getting your own VPN service.

You’re right, Popcorn Time does have seeding capabilities, but it’s not turned on by default.

And the version of popcorn time that has the malware is the rebranded Time4Popcorn. The one on popcorntime.io seems legit and also offers the VPN option, though it is a paid subscription for that.

I’d be curious to hear your take on the consequences of peer-to-peer downloading. You’ve passed over it here.

I’ve never once streamed a video that couldn’t easily be copied from whatever temporary folder it exists in while you are watching it (after it finishes fully loading of course). There is no such thing, all streamed video still involves downloading the whole video, assuming you allow it to finish completely loading. A copy is always produced on your computer, and simply deletes itself when you close the browser or tab. If you navigate to the temporary folder before closing the browser, the full video will be there and can be copied. This applies to ALL streaming. There are also browser plugins that give this functionality right in the browser, allowing you to place a copy of the video right in your downloads folder.

Thanks god for streaming (legit sites or otherwise) – it’s the only way I can watch many blacked-out NHL games.

Altho regional blackouts are an entirely different beast, I suppose. Such an antiquated concept, at any rate.

Pingback: Monday Pick-Me-Up « Legal Sourcery

Get real here.

Copyright law is about distributing material.

Peer to peer, distribute material.

Listening to a stream, don’t distribute anything so the user can view it without consequence. Peer-to-peer had put the copyright burden over the peer, but before that, when a website was distributing copyright material, only that website was responsible for a copyright breach (aka distributing).

Uploading of copyright material is not okay in Canada.

Dowloading anything from anywhere is okay in Canada.

Pingback: Canada's New "Notice and Notice" Regulation & Worldline - Worldline Canada

Thanks for confirming about end users, we have had a recent example in Aus where a copyright holder has won the right from a court to recive the details of over 5000 people who downloaded via peer to peer, whilst there is concern, many legal pundits are saying the damages that would be payable, if the copyright holder even managed to enforce these damages could be as low as $10 or $20.

I found in the EU that they’ve pretty well had streaming covered since 2001 with this

Article 5 of Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2001 on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society must be interpreted as meaning that the copies on the user’s computer screen and the copies in the internet ‘cache’ of that computer’s hard disk, made by an end-user in the course of viewing a website, satisfy the conditions that those copies must be temporary, that they must be transient or incidental in nature and that they must constitute an integral and essential part of a technological process, as well as the conditions laid down in Article 5(5) of that directive, and that they may therefore be made without the authorisation of the copyright holders.

One thing is for certain – times have changed and we will never go back to paying for content like we were in the past