As the negative coverage of the government’s surprise decision to extend the term of copyright for sound recordings and performances mounts (Billboard, National Post), it is worth remembering that it is Canadian consumers that will bear the costs with decreased choice and increased prices. I touch on this in my weekly technology law column (Toronto Star version, homepage version), but a more detailed discussion is warranted (see here, here, and here for previous posts on the proposed extension).

The question of competition and consumer costs was addressed in several leading European reports on intellectual property and term extension. The University of Cambridge’s Centre for Intellectual Property and Information Law reviewed the economic evidence related to term extension for sound recordings, stating:

When a music company or artist earns more because of a term extension that money must come from somewhere. Crudely, there are only two possibilities. On the one hand, the money came from some other firm, perhaps the “public domain specialist”, who, in the absence of a term extension, would have been able to enter the market for as a seller of the recording. On the other hand, the money came from end-users who without a term extension would have been the recipients of lower prices. Theory inclines us towards the second possibility: greater competition to supply a recording once it enters the public domain should operate to drive down prices, transferring value from producers to consumers.

The Gowers Review of Intellectual Property, a leading independent UK report, comes to much the same conclusion:

As sound recordings of enduring popularity enter the public domain, economic theory suggests that competition between many release companies will drive down the price, just as has occurred in the public domain book market for classic literature. Therefore, the review believes that most of the increased revenue from term extension would come directly from consumers who would pay higher (i.e. monopoly) prices for longer.

So did a report for the European Commission conducted by the Institute for Information Law at the University of Amsterdam, which noted:

when the exclusive reproduction right for phonograms expires, any competing record company can make use of it and release the same recording potentially at lower prices. An extended protection would prolong the temporary monopoly of the original phonogram producers, preventing the downward pressure of competition on prices. As a result, consumers would continue to pay higher prices for certain sound recordings for several years.

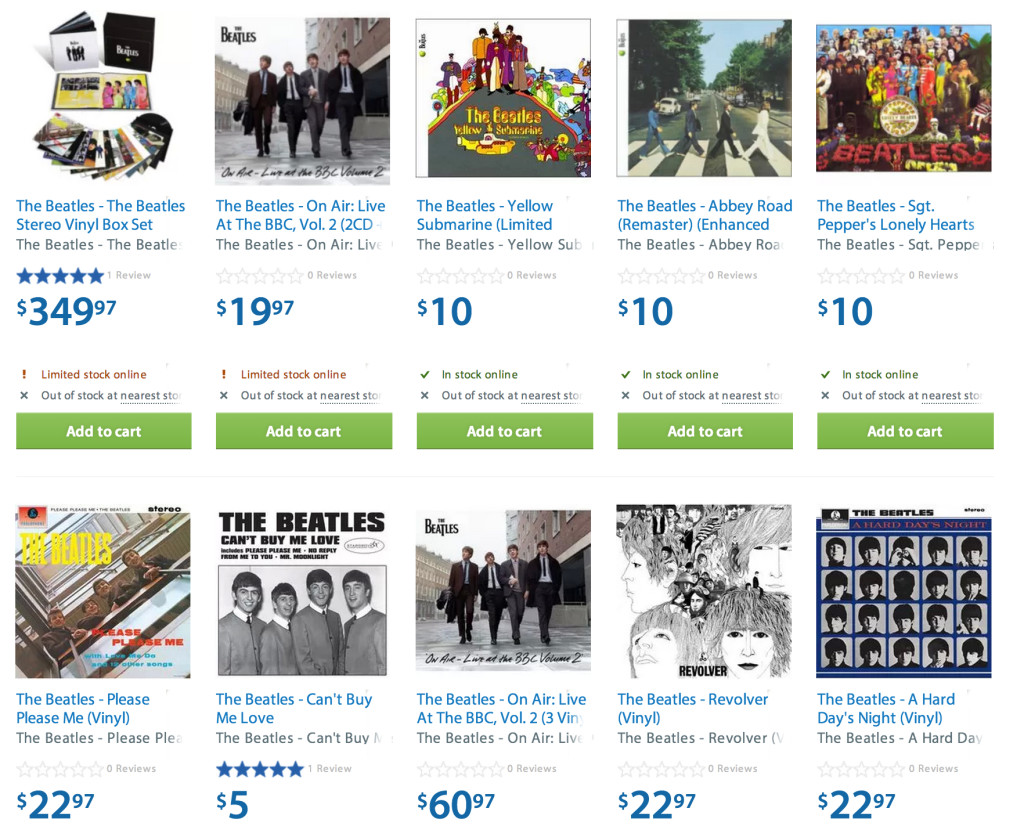

Canadian consumers are seeing this issue unfold right now at Walmart Canada. A search for the Beatles reveals many choices, the overwhelming majority of which are offered by Universal Music, the international record giant. But consider these results and guess which is not offered by Universal Music.

The answer is unsurprisingly the $5 record, which is far cheaper than anything else being offered. It is a public domain record released by Stargrove Entertainment featuring 11 songs, virtually all written by Lennon and McCartney. The composers are paid royalties for their work. What distinguishes this record is that it is a non-Universal record offered at a much lower price.

As the Gowers review predicted, public domain recordings encourage competition between release companies and drive down the price for consumers. The songwriters are paid either way, but the consumers win with more choice and lower priced music. Increased competition is good for consumers and for the creators of the songs, yet the government’s decision to extend the term of copyright for sound recordings effectively reduces choice and eliminates competitors. Given the outcome that generates profit for record companies decades after their investment at the expense of consumers, it should come as little surprise to find that Music Canada, the lead record company lobby group, engaged in extensive lobbying with the Director of Policy at the Minister of Canadian Heritage in the months leading up to the budget. More on their lobbying campaign in an upcoming post.

Is it just me, or are other people galled by the fact that years in the case of movies and decades upon decades in the case of music, premium prices are still asked for? For instance, just how much do you suppose Avatar has made? I’m talking about theatres, downloads, B-ray. And yet, the 3D B-ray is still going for $30 CAN. Seriously? And seriously, Beetles junk still going for $20? Have you not finished making your money on these trite pieces of junk yet? How many more centuries must you charge so much for this stuff?

It all comes down to greed of course. Untold millions have been made, massive returns on the money and effort spent and still the prices gall. Hey, I’m all for charging for what you did but at some point, you have to drop the prices. I understand that if you drop it too soon, people will just wait. Well, some will and most won’t. But decades later, you still want this much money for something that’s barely worth listening to. Greed at it’s worst.

Patricia – I understand the point you are trying to make and agree – to a degree – with the conceps. But I am going to take umbrage with your use of “Beetles (sic) junk” and the connotation that the Fab Four’s music is/are “trite pieces of junk.” While music is subjective and you are entitled to your opinion, nothing could be further from the truth. Like many I am not happy that I bought many albums on multiple formats (from LP to Casette to CD to MP3) and in turn gave – & with this extension will seemingly continue to give – Apple (Records), Universal, Sony, et. al. a healthy margin they likely saw many times over. However, I will continue to purchase quality recording ‘In my Life.’

Why would anyone buy music today? It’s called you tube.

Because there’s no shortage of chumps out there. Never mind that 99,9 percent of us see the whole thing for what it really is. If in that sampling of a thousand, only one rushes in, the snake oil salesman is in business.

How many artists will fail to produce new music or innovate because their descendants can only make money for 50 years after their death?

The answer is a pretty obvious, “none at all.”

Copyright extensions add no value to musical recordings, nor do they encourage innovation and creation. Copyright extensions only serve to bolster and industry that has a long track record of NOT innovating and NOT encouraging creativity. Shorter copyright terms can only encourage innovation and creativity by forcing the industry to be more discriminating and creative, while spurring innovation in secondary industries as distributers and marketers are forced to find new and better ways to reach the consumer.

Really, we should be looking at copyright reductions. Bring the term down to 25 years, or even 5 years after death. No artists will be harmed: Only the consumer will benefit.

“…all written by Lennon and McCartney. The composers are paid royalties for their work. ”

I’m just curious…

How are they paying Lennon, exactly?

: )

I’m guessing it goes to the estate.

If they were serious, they’d extend to 70 years only for new recordings. When the Fab Four did their albums, they did them expecting 50 years. There’s no reason for society to bear more.

Pingback: Canada’s Copyright Extension: Intellectual Property is Pure Policy | Secret Spaceman

A metaphor I asked a boss of mine one day was, Could I receive wages for work I performed ten years ago? the answer was no. This is in a feeble effort to agree with the point that someone posted concerning how long do we have to pay for an artist’s recording made even twenty or maybe even forty years ago. With this in mind I have suggested that ten years is long enough for copyrights on books, music, movies, or whatever else that would fall into this kinda production. I may be opening my big mouth as they say, but it is a wonder that when I borrow a book form a library, that I have pay a royalty on that book I am borrowing .