Privacy laws around the world may differ on certain issues, but all share a key principle: the collection, use and disclosure of personal information requires user consent. The challenge in a digital world where data is continuously collected and can be used in a myriad of previously unimaginable ways is how to ensure that the consent model still achieves the objective of giving the public effective control over their personal information.

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada released a discussion paper earlier this year that opened the door to rethinking how Canadian law addresses consent. The paper suggests several solutions that could enhance consent (greater transparency in privacy policies, technology-specific protections), but also raises the possibility of de-emphasizing consent in favour of removing personally identifiable information or establishing “no-go” zones that would regulate certain uses of information without relying on consent.

My weekly technology law column (Toronto Star version, homepage version) notes that the deadline for submitting comments concludes this week and it is expected that many businesses will call for significant reforms to the current consent model, arguing that it is too onerous and that it does not serve the needs of users or businesses. Instead, they may call for a shift toward codes of practice that reflect specific industry standards alongside basic privacy rules that create limited restrictions on uses of personal information.

Suggestions from Canadian business that stronger consent rules are too difficult or costly is nothing new. During the heated debate over anti-spam legislation, the business community claimed that an “opt-in” model of consent that would require a more explicit, informed agreement from users would be expensive to implement and would create great harm to electronic commerce. Yet the reality is that the opt-in model is used in many other countries to provide better privacy protection and improve the effectiveness of electronic marketing.

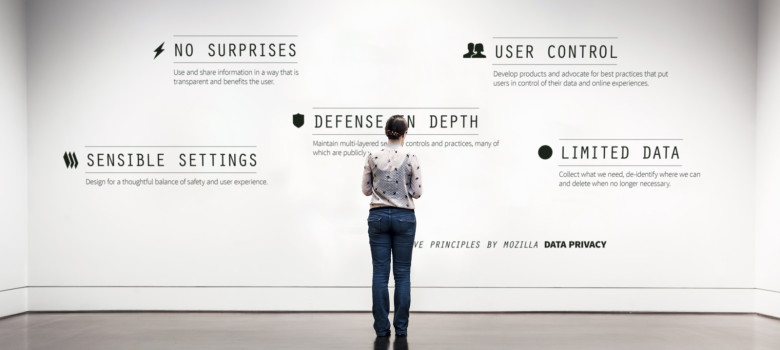

Rather than weakening or abandoning consent models, Canadian law needs to upgrade its approach by making consent more effective in the digital environment. There is little doubt that the current model is still too reliant on opt-out policies in which business are entitled to presume that they can use their customers’ personal information unless they inform them otherwise. Moreover, cryptic privacy policies that leave the public confused about how their information may be collected or disclosed creates a notion of consent that is often based on fiction, not fact.

How to solve the shortcomings of the consent-based model?

First, Canada should implement opt-in consent as the default approach. At the moment, opt-in is only used where strictly required by law or for highly sensitive information such as health or financial data. The current system means that the majority of information is collected, used, and disclosed without informed consent.

Second, since informed consent depends upon the public understanding how their information will be collected, used, and disclosed, the rules associated with transparency must be improved. Confusing negative-option check boxes that leave the public unsure about how to exercise their privacy rights should be rejected as an appropriate form of consent.

Moreover, given the uncertainty associated with big data and cross-border transfers of information, new forms of transparency in privacy policies are needed. For example, algorithmic transparency would require search engines and social media companies to disclose how information is used to determine the content displayed to each user. Data transfer transparency would require companies to disclose where personal information is stored and when it may be transferred outside Canada.

Third, effective consent means giving users the ability to exercise their privacy choices. Most policies are offered on a “take it or leave it” basis with little room to customize how information is collected, used and disclosed. Real consent should also mean real choice.

Fourth, stronger enforcement powers are needed to address privacy violations. The rush to comply with the Canadian anti-spam law was driven by the inclusion of significant penalties for violation of the rules. The general Canadian privacy law is still premised on moral suasion or fears of public shaming, not tough enforcement backed by penalties. If privacy rules are to be taken seriously, there must be serious consequences when companies run afoul of the rules.

As an individual concerned with my own privacy and an information security professional concerned with the ability of the information industry to properly protect the personal information of individuals they interact with, this topic is of great concern to me.

I should like to make two comments on the topic of personal information.

First, your 3rd point should be the first and most important point of discussion where consent is concerned. Which is to say, “effective consent means giving users the ability to exercise their privacy choices. Most policies are offered on a “take it or leave it” basis with little room to customize how information is collected, used and disclosed. Real consent should also mean real choice.”

If I choose to communicate with an organization in such a way that I provide “personal information” or that personal information about it is communicated (many times without my knowledge), then I should never be required to agree to have that information shared with a 3rd party except where that sharing is necessary for and restricted the effective delivery of the communications.

My second point is in agreement with the organizations opinion that opt-in and informed consent are too difficult. However, I do not for one minute believe they are too difficult for the organizations to implement from a technology or business perspective. They are too difficult for the average internet user to properly comprehend in the current model.

With the above to points in-mind, it is my opinion that the only fair form of consent is one of obvious-single-purpose-implied consent.

Allow me to illustrate:

If I purchase some items while online shopping and I enter in shipping and billing information, I have given obvious and implied consent to use that information for billing and shipping purposes only. As it relates to that transaction, I have probably created an account with the online retailer and provided an e-mail address for the purpose of managing my account (such as password resets and receiving shipping noticed).

Regardless of anything written in a privacy policy, opt-in, or opt-out checkboxes, it is not obvious or implied that I have given consent to receive notifications of new products, sales, or affiliate advertising. Nor is it obvious or implied that I have agreed to let my personal information be shared for for marketing purpose.

My point is it must be “obvious” in that an individual who is in a rush and not paying attention to details.

It must be single purpose. Otherwise the consent is not a true choice.

This does not preclude the online retailer from offering me the opportunity to receive their notices of new products and sales. It simply means that requesting that must be a separate and obvious single-purpose action on my part as a consumer (and there are a number of online retails that I have chosen to receive such notifications).

Is this ideal, no.

The businesses won’t like it because they will perceive it as harder to get people to sign up for their marketing announcements. Of course, the people who do sign-up will be far more interesting in receiving what they have to send.

The end-users will find it a nuisance to have to re-enter their details for different services offered by an organization but they won’t be confounded by unreadable and confusing privacy policies. Any wording which makes lawyers happy is almost always confusing to the rest of us.

The whole conversation about consent is futile. I don’t even know why anyone engages in it anymore.

Everyone has been gobbling up and using everyone’s information for ages now, regardless of whether consent has been given or not, and this practice will never stop, no matter how much anyone kicks and screams to anyone else about it.

Once companies began the process of tracking info and other things specific to the users, the stage was already set for abuse, and no real oversight was ever given to this activity – not by governments, or the courts, or other groups. What little law that was set on the subject never yielded any real deterrents to this process, nor any mechanism of punishment for abusers.

Everyone will continue to collect everything, use it, and share it with everyone else, simply because they can do so without concern for anyone’s objection. All parties who have an interest in mining, using and sharing your data publish their “privacy policies” as a form of lip service. That’s all.

Pingback: Monday Pick-Me-Up « Legal Sourcery

one thing NOT mentioned is “policing” privacy in Canada for Canadian e-tailers is ONE thing BUT what about the “global” operations that will just MOVE out of Canada and be foreign ONLY

they could “dress up” a Canadian LOOKING site but actually run out of a foreign country and be under their laws NOT ours