Last week’s CRTC decision on group licensing for the major Canadian broadcasters has the creative community in a panic, claiming that it could “mean the devastation of Canadian domestic [television] production.” The decision, which set a uniform spending requirement of 5 percent on programs of national interest (PNI, which includes dramas, documentaries, some children’s programming, and some award shows), means a reduction in spending requirements for some broadcasters. The Writers Guild of Canada fears that the decision could lead to a reduction in spending on PNI of $200 million over five years.

Groups have heaped criticism on CRTC Chair Jean-Pierre Blais, whose term ends next month. The WGC labels him a “Harper appointee”, while Kate Taylor says “he doesn’t leave much of a legacy for himself” and that “his piecemeal approach offers no consistent strategy to address the challenges facing Canadian television production in the Netflix age.”

Blais may have his faults, but claiming that he has not had a strategic vision for the digital age is not one of them. He recognized that the advent of the digital networks, an abundance of consumer choice, and the effective removal of longstanding analog protections for Canadian creators would gradually reduce the relevance of the regulator and leave it with two choices. The first – favoured by the creator groups – was to temporarily prolong the protections by extending Cancon regulations to Internet services and increasing regulatory costs on broadcasters. The second was to jump on the digital bandwagon, gradually removing the safeguards and creating a regulatory environment premised on competition at all levels – creators, broadcasters, and broadcast distributors. Anyone following the CRTC broadcast and telecom decisions in recent years knows that he chose the latter.

The result is a digital regulatory framework designed to enable Canadian creators to compete on a level playing in Canada (net neutrality), encourage the creation of programming that finds international audiences and partnerships (TalkTV), grant consumers greater television choice (skinny basic and pick-and-pay) and more competitive Internet services (wholesale fibre access), ensure universal Internet access (TalkBroadband), maintain deregulation of Internet-based services (new media exemption), facilitate new Canadian Internet entrants (hybrid services), and press broadcasters to reduce their reliance on U.S. programming (simsub). The policies may not universally succeed (and the simsub decision did not go as far as he may have wanted), but there is no doubting the strategy. In fact, despite the expectation that some have for Canadian Heritage Minister Melanie Joly to chart a new path, most of her public comments on digital Cancon are headed in the same direction.

Is 5 percent for PNI too low? At least four things can be said to defend the decision and place the impact into proper perspective. First, the argument that broadcasters needed a lower PNI number to compete with Internet-based services such as Netflix has merit. There are good reasons for not creating a mandatory contributions requirement for Internet video services, but the cost gap between regulated and unregulated services is relevant to the setting of mandated contributions for regulated broadcast services. Further, the decision lends credence to those who regularly whispered that the lobbying campaign for a Netflix tax was never about the money that could be generated from the streaming giant (a five percent tax on Netflix Canadian revenues generates a tiny amount of money given that Canadian TV production is a $2.6 billion industry) but rather about maintaining the contributions for the regulated services. When the licences come up for renewal in five years, the calls for the elimination of any contribution in the face of unregulated competition will be far louder.

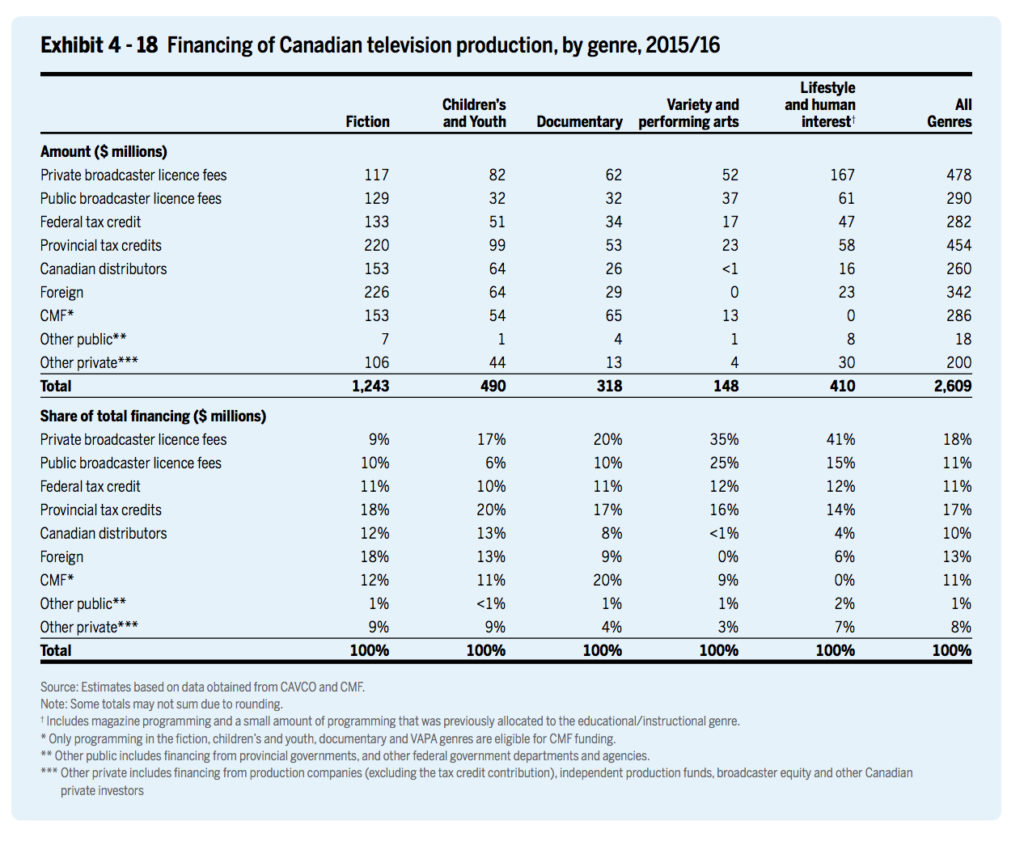

Second, the suggestion that the Canadian television industry is – as Kate Taylor’s column states – “left to fend for themselves” ignores the massive public support for Canadian content creation. Given the amount invested annually by Canadian taxpayers, it is simply not credible to claim that Canadian television has been abandoned. The CMPA’s Profile 2016 tells the story with well over a billion dollars contributed from public sources including the public broadcaster, federal and provincial tax credits, and the Canadian Media Fund.

Third, while the industry is clearly not left to fend for itself, the CRTC decision is part of a shift that encourages and rewards success, not just creation. The claim that reduced mandatory PNI will devastate the industry is premised on the notion that Canadian broadcasters will only invest in domestic programming if required to do so. Licensing cheaper foreign programming is understandably attractive, yet the long-term success of broadcasters increasingly depends on controlling original content that can be delivered through multiple channels and markets (particularly if simsub disappears). In other words, the market encourages investment in original programming and the CRTC has sought to establish conditions that promote such investment.

Fourth, critics of the decision are quick to point to higher profile Canadian fictional programming that is said to be at risk, but the CMPA data confirms that private broadcasters are relatively minor players when it comes to the financing of Canadian drama. The report states:

With fiction productions, the largest share of financing came from provincial and federal tax credits; the fiction genre also attracted the most foreign financing among all genres. Children’s and youth productions also derived the largest share of their financing from tax credits, followed by broadcaster licence fees. Distributors also accounted for an important part of the financing picture for the fiction, and children’s and youth genres. In the VAPA and lifestyle and human interest genres, most financing came from broadcaster licence fees.

The CMPA chart below confirms that conclusion with private broadcasters contributing only 9 percent of the financing for fictional programs, less than federal and provincial tax credits, Canadian distributors, foreign financing, and the CMF. Private broadcasters allocate much of their money toward variety and performing arts as well as “lifestyle and human interest” programming, which including magazine style shows.

CMPA Profile 2016, Page 54, http://www.cmpa.ca/sites/default/files/documents/industry-information/profile/Profile%202016%20EN.pdf

In other words, financing and the success or failure of Canadian programming such as dramas do not depend upon private broadcaster spending. In fact, the WGC release effectively confirms this since their worst case scenario – $40 million in reduced broadcaster PNI spending per year – represents just a two percent reduction in total financing for the fiction, children’s and documentary genres in Canada at a time when foreign funding from services such as Netflix is on the rise. Hardly the stuff of devastation.

It’s always the legacy model demanding some sort of protection or compensation from the newer business models. Their own words just scream of entitlement…

“…his piecemeal approach offers no consistent strategy to address the challenges facing Canadian television production in the Netflix age.”

What a statement like that really says is, “Protect us from Netflix!” As if competition is something they’re not supposed to expect?!

It’s not about protection from Netflix. They produce plenty of content in Canada, providing jobs to Canadian crew and helping strengthen the economy overall. But the problem is that Netflix is not treated like a broadcaster because it’s done over the internet. But for all intents and purposes, they are a broadcaster. So they don’t have to pay into the system like the others.

Competition is expected, and in many ways it’s a good thing. But we have a country to our south that has 10x as many people and more than 10x the amount of money spent on production. We, as a country, have a hard time competing with that, but we also have our own culture that is distinct from theirs. If we don’t do something to pay into a system that creates and encourages Canadian production, we’ll have nothing but American shows on our TVs and nothing that reflects our values.

I know that there’s a wide diversity of people across Canada, and people believe in and care about all sorts of things… but if you try telling me that we truly hold the same values as the United States, then I guess my argument will be entirely lost on you.

Pingback: Canadian TV in the Netflix Age: In Defence of the CRTC Television Licensing Decision – Michael Geist – Angry Robot

The problem with Jean-Pierre Blais’ vision of the Canadian broadcasting future is that it leaves little place for high quality indigenous Canadian production. Lower Canadian content requirements in terms of hours broadcast and spending will only encourage reliance on more U.S. programming. The damage began with the results of the Let’s Talk TV proceeding and has been confirmed by the May 15 licence renewals of the television services owned by the large broadcasting ownership groups. Contrary to what Michael Geist asserts, net neutrality is a telecommunications issue concerning differential pricing by Internet service providers (ISPs) that has no direct implications for Canadian creators of high quality television programs.

The production of high quality indigenous Canadian television programs in the under-represented categories (drama, POV documentaries, children’s programs) has been relatively successful over the last two decades, largely due to case-by-case CRTC requirements and government financing from tax credits and institutions such as the Canada Media Fund. A television broadcaster’s commitment to air such programs is necessary to obtain Canada Media Fund, and federal and provincial tax credits, among other funding sources.

The legacy of Jean-Pierre Blais will be to have precipitated the decline of under-represented programs (aka programs of national interest). Blais has implemented a populist agenda focused on lower prices for consumers as if television broadcasting should be guided by the economic objectives and purpose of the Telecommunications Act and the Competition Act, rather than the cultural objectives of the Broadcasting Act. In accordance with this agenda, lower prices for consumers are provided in the form of less Canadian content (which is more expensive to produce than acquiring U.S. programs) and more laisser-faire. Despite the rhetoric, there is nothing innovative about this libertarian itinerary.

Jumping on the digital band wagon, as Micheal Geist advocates, means killing off high quality indigenous Canadian production – without a replacement. Digital media generate relatively little high quality original content (in terms of total hours broadcast), and very almost no high quality identifiably Canadian content. Netflix, for example, broadcasts a small number of high quality American original prime-time tv shows backed by a library of U.S. movie and television series reruns. Once we get past the Silicon Valley agitprop, Netflix is no more than an unlicensed television channel offering subscription video-on-demand (S-VOD). It does not produce identifiably Canadian content in any significant volume. Why should Netflix and other such U.S. programming services get a free ride in Canada?

Without the equitable treatment of Canadian and non-Canadian television programming services, the protection and enhancement of Canada’s distinct identity will be diminished. The solution is to gradually bring digital programming services into the Canadian television broadcasting environment. This could begin with governments applying federal and provincial sales taxes to programming services. The CRTC could treat Internet programming services as VOD programming undertakings – exempting such services subject to their meeting certain requirements. The Commission has already created a category of hybrid VOD services which could serve as a model for this kind of approach.

Canadian broadcasters on the basic service, such as CBC, CTV, Global, Radio-Canada and TVA, generally invest in high quality original Canadian programs. Not only is their production financing crucial, but so is their emotional commitment, promotion and scheduling. However, unlike these basic services, the discretionary and on-demand services do not have strong incentives to create original programming in the under-represented categories, unless the CRTC directs them with precise conditions of licence. These services will only invest in high quality original Canadian programming if required to do so. Thus, for example, three days after the CRTC announced the licence renewal of Séries+ for the next five years, relieving the French-language specialty service of its obligation to spend $1.5 million a year on original Canadian drama, its owner, Corus Entertainment of Toronto, cancelled all three of Séries+’s projects in development. http://www.journaldemontreal.com/2017/05/18/series-bientot-sans-contenu-quebecois No requirement, no more spending.

With his approach to the licence renewal of the television services owned by the large broadcasting ownership groups Jean-Pierre Blais has contributed to the dismantling of the current television broadcasting system and its replacement with fewer original Canadian programs in the high cost under-represented categories, such as drama. This will lead to reduced opportunities to view Canadians on television and a consequent loss in our national sovereignty and identity.

Pingback: Jean-Pierre Blais’ Term as CRTC Chair – Michael Geist blog – FirstMile

Pingback: Good Politics, Bad Policy: Melanie Joly Sends TV Licensing Cancon Decision Back to the CRTC - Michael Geist

Pingback: Good Politics, Bad Policy: Melanie Joly Sends TV Licensing Cancon Decision Back to the CRTC – Debrah Nesbit