The government’s consultation on reform to the Copyright Board of Canada recently closed with a plan for reform expected to be unveiled in the coming months. My submission to the consultation is posted below. It focuses on two areas. First, it emphasizes the overriding goal of any public institution or administrative tribunal: serving the public interest. In doing so, it points to three issues: public participation, the independence of members of the Copyright Board, and regulation and transparency of copyright collectives.

On this last issue, I note the close linkage between the parties that appear or are affected by board decisions and reform of the board itself. While the consultation document maintains that governance of collecting societies is beyond the scope of the consultation, I argue that solely addressing administrative powers wielded by the board without also assessing the rules pertaining to participation before the board will not adequately address concerns regarding the function of the board itself. In other words, the who and the how are inextricably linked and must be addressed concurrently.

A Consultation on Options for Reform to the Copyright Board of Canada

I am a law professor at the University of Ottawa, where I hold the Canada Research Chair in Internet and E-commerce Law. I focus on the intersection between law and technology with an emphasis on digital policies, particularly copyright. I have appeared before many committees on copyright policy and edited several books on Canadian copyright policy.

This submission, which is based on several earlier public posts, columns, and an appearance before the Senate Standing Committee on Banking, Trade, and Commerce, focuses on two areas. First, it focuses on the overriding goal of any public institution or administrative tribunal: serving the public interest. In doing so, it points to three issues: public participation, the independence of the Copyright Board, and regulation and transparency of copyright collectives.

On this last issue, I emphasize the close linkage between the parties that appear or are affected by board decisions and reform of the board itself. While the consultation document maintains that governance of collecting societies is beyond the scope of the consultation, I argue that solely addressing administrative powers wielded by the board without also assessing the rules pertaining to participation before the board will not adequately address concerns regarding the function of the board itself. In other words, the who and the how are inextricably linked and must be addressed concurrently.

Background

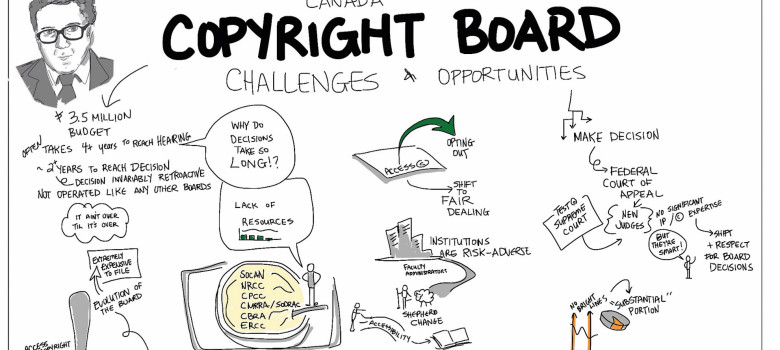

As the consultation document rights notes, there is no shortage of criticism of the Board. Indeed, in an field that is often sharply divided, disenchantment with Board is sometimes the one thing people seem able to agree on. The criticism typically comes down to two issues: the substance of decisions and the way those decisions are rendered. The government should pay little attention to substantive criticism of Board decisions. As former Chair of the Board Vancise noted last year, criticism of the substance of decisions usually comes down to “whose ox is being gored.” If you like decision, you’re comfortable with the Board. If not, you think the Board is dysfunctional and in need of an overhaul.

I have been both critical and supportive of past Board decisions. I think the Board was initially very slow in acknowledging and implementing the copyright decisions delivered by the Supreme Court of Canada, particularly around fair dealing. That has changed, however, and the decisions are now more reflective of the court’s jurisprudence. Decisions are and will continue to be challenged, yet we should recognize that there is an established system to address appeals. Reform isn’t needed on the substance of decisions.

Contrast the substantive concerns with the administrative ones. How the Board reaches decisions, the costs involved, the timeliness of those decisions, and the ease of participation is very much a matter for review.

From my perspective, there is unquestionably a need to develop reasonable timelines for conducting hearings and issuing decisions. At times, there may be parties that are content to “rag the puck” without any urgency on Board processes. Given the importance of Board decisions beyond the immediate parties, timeliness is crucial. Providing the Board with the powers to maintain timeliness of procedures is important and the proposals in the consultation document should assist in addressing the timeliness of decisions.

The Board and the Public Interest

The consultation paper frames the role of the Board in the following manner:

In performing its functions, the Board facilitates the development and growth of copyright-based markets in Canada, resolves disputes between market actors and protects the public interest.

With respect, much like the Copyright Act itself, the primary goal of the Board is to further and protect the public interest. It is in the public interest to facilitate the development and growth of copyright-based market and to resolve disputes between market actors. However, the importance of the public interest should not be viewed as one of the board’s functions, but rather its primary one. In prioritizing the public interest, there is scope to address the interests of all stakeholders, including the creators and users that regularly appear before the Board. It also ensures that the Board’s work considers the broader implications of its decisions and processes, thereby facilitating wider participation and support for copyright administration.

In this sense, the Board is no different than any other tribunal, agency or government policy, who are all ultimately about serving the broader public interest. A narrowly defined vision that elevates the interests of certain stakeholders or policy priorities above the over-arching public interest goal runs the risk of lost public confidence in the process and missed opportunities to further Canada’s broader copyright policy goals.

This submission focuses on three mechanisms that would further the Board’s facilitation of the public interest: maximizing public participation, ensuring the independence of Board members, and fostering transparency of copyright collectives in the interests of both creators, users, and the broader public.

i. Maximize Public Participation

Ensuring the board fulfills its mandate to serve the public interest, can be addressed in several ways but none is more important than opening the door to broader public participation. The government has identified the need for public participation in policy processes as one of its top priorities. Indeed, the mandate letters of all government ministers emphasized the importance of openness, transparency, and consultation. Since the 2015 election, the government has worked hard to meet its commitment to public participation by conducting numerous public consultations on a wide range of issues.

This emphasis on public participation can be contrasted with the Board, where hearings and activities are largely limited to a small group of stakeholders who invest heavily in the process. The effective exclusion of the public stands in sharp contrast to the other boards, tribunals, and agencies that address issues with individual parties but whose decisions have ramifications for a far broader group of stakeholders.

For example, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) and the Competition Bureau of Canada have both taken steps in recent years to involve the public more directly in policy making activities, hearings, and other issues. In the CRTC’s recent differential pricing hearing, it found a number of ways to engage the public, including discussions on the website Reddit. All of this participation enters the public record, allows for better informed decision making, and leads to greater confidence in the decisions themselves. By contrast, the Board does little to encourage public participation, despite the fact that its decisions often have an impact that extends beyond the parties before it.

When asked several years ago about accessibility and participation concerns, the Board pointed to a working group as evidence that it regularly reviews its practices and compared itself to the Federal Court of Appeal, noting that “of course they [the public] don’t participate, because they don’t really belong there, per se.”

With all respect, I think the Board is wrong and the lack of emphasis on public participation a shortcoming of the consultation document. The impact of the Board’s decisions extend far beyond the limited number of parties that participate in the hearing. The most obvious stakeholders are intellectual property lawyers and copyright collectives, but decisions have a direct impact on commercial users, on the broader public, and on our understanding of copyright law. This in turns implicates consumer pricing as well as copyright practices on issues such as fair dealing and the public domain.

Many branches of government and administrative agencies have recognized the need to engage the public and to develop better decision making processes by maximizing public participation and engagement. To date, the Board has not done so. Its processes are costly, lengthy, and for all practical purposes inaccessible to the general public. That needs to change.

The CRTC provides a good model for enhancing public participation. Its participation funding approaches for both telecom and broadcast allow for public interest groups to appear, retain experts, and ensure that a broader perspective is included within the hearing process. The funding models place the cost burden on larger, wealthier participants such as telecommunications companies. In the Board context, developing a mechanism to create a board participation fund supported by all commercial stakeholders should be a top priority.

Moreover, public participation and engagement must become a core part of the Board’s practices with rules that enable innovative forms of participation that lower the bar to participation and ensure that the broader public interest and perspective is included in the Board’s deliberations and decision making. Courts have well established processes for intervenor status to allow broader participation in decision making and hearings. Those perspectives should be included in the Board’s decision making process, not wait for appellate hearings of Board decisions when these views are later brought into the record through interventions at the Federal Court of Appeal or the Supreme Court of Canada.

ii. Board Member Independence

The government’s recent announcement that it plans to fill vacancies at the Board is to be welcomed by all stakeholders as a fully functioning board can better serve the public interest and the goals of enumerated in the consultation document.

In working to identify new board members, it is essential that any new board member be fully independent. I recognize that there are frequently tensions between identifying qualified, experienced board members (who may often have a history of working in the sector) and ensuring full independence of the members of the board. A call for full independence is not meant to suggest that current or past members have been viewed as something less than independent. However, tribunals and boards may run the risk of losing public confidence where the “regulated become the regulator.”

Experience and expertise in the field is important, but independence is the essential ingredient in fostering public confidence in decision making. I would argue that prospective board members that have represented or worked for groups that regularly appear before the Board should refrain from sitting on the board itself. While this may heighten the challenge of identifying suitable candidates, the result will better ensure that the public interest is served.

iii. Copyright Collective Transparency and Regulation

The consultation document states:

Potential changes to the governance of collective societies more generally and the existing system for granting licences in respect of copyright belonging to owners who cannot be located are also beyond the scope of this consultation.

With respect, effective Board reform should not be limited to board procedures and processes. Serving the public interest and gaining the confidence of the wider copyright community also depends upon the confidence in key stakeholders who serve as intermediaries in the administration of copyright. Given the interests of creators to be paid and users to ensure that their payments reach those creators, the role of copyright collectives is closely connected to the effective functioning of the Board.

The challenges associated with confidence in the management and transparency of copyright collectives represents a global concern. For example, the Australian copyright community was shocked by a scandal earlier this year involving the Copyright Agency, a copyright collective that diverted millions of dollars intended for authors toward a lobbying and advocacy fund designed to fight against potential fair use reforms. The collective reportedly withheld A$15 million in royalties from authors in order to build a war chest to fight against changes to the Australian copyright law. A former director of the Copyright Agency described the situation as “pathetic” noting that it was outrageous to extract millions from publicly-funded schools for a lobbying fund.

The Australian case is far from an isolated incident. In recent years, there have numerous examples of legal concerns involving copyright collectives with corruption fears in Kenya and competition law concerns in Italy over the past couple of months as well as recent fines against Spanish collecting societies. In fact, studies have chronicled an astonishing array of examples of corruption, mismanagement, lack of transparency, and negative effects for both creators and users from copyright collectives around the world.

Canada is home to an enormous number of copyright collectives and the allocation of revenues toward lobbying may also be an issue here. For example, this year’s Access Copyright annual report re-names the longstanding expense on copyright tariffs as “Tariff, litigation and advocacy costs”, better reflecting expenditures on lobbying and advocacy activities in which the organization lines up against fair dealing and in favour of copyright term extension. Since the introduction of copyright reform in 2010, Access Copyright has reported spending nearly $7 million on litigation that has been largely unsuccessful, tariff applications, and government lobbying and advocacy (the specific amounts totalling $6.81 million are 2016: $641,000, 2015: $443,000, 2014: $826,000, 2013: $1,571,000, 2012: $1,221,000, 2011: $1,459,000, 2010: $730,000).

There has been no evidence or reason to think that the full-scale corruption elsewhere has occurred in Canada. Indeed, there is every reason to think that Canadian copyright collectives and their administrators are deeply committed to representing the best interests of their members. However, over the past decade there has been concerns voiced in some quarters about the management and transparency associated with Canadian copyright collectives.

For example, in 2008, Professor Martin L. Friedland conducted a study of Access Copyright, calling for dramatic change in governance, transparency, and royalty distribution practices. Friedland began by noting:

I have undertaken a number of other public policy studies over the years, including such reasonably complex topics as pension reform, securities regulation, and national security, and have never encountered anything quite as complex as the Access Copyright distribution system. It is far from transparent. Very little is written down in a consolidated, cohesive, comprehensive, or comprehensible manner. There is no manual describing in detail how the distribution system operates.

The report continued by examining the history of Access Copyright, comparing it to other collectives, and identifying inequities in the distribution structure. For example, it reveals that “in the distribution for 2005 under the federal government licence, the publishers received $188,256 for scholarly journals and the creators received nothing.”

The report included 20 recommendations for change. To its credit, Access Copyright made many reforms in response to the report, including significant changes to its board structure. Yet that same year, the League of Canadian Poets and Access Copyright battled publicly over the copyright collective’s allocation policies. In a letter dated September 22, 2008, the League said that it was “calling for a formal, public, government audit, annual review and effectiveness audit of Access Copyright.” It added that it is their “understanding that there are staff members at Industry who are going to look at ‘collectives’ in the next phase of Copyright Act reforms. Please look at Access Copyright first.”

The issues associated with copyright collectives were never fully addressed in the 2012 copyright reform process. Ensuring that the Board serves the public interest should include developing regulations regarding transparency and appropriate regulation of copyright collectives, whose intermediary role is frequently the final step between a Board ruling, user payment, and the distribution of funds to creators.

Other jurisdictions, including the European Union, Australia, and Japan use regulation or codes of conduct to address transparency and conduct concerns. A 2012 study for the British government by Professor Brian Fitzgerald on regulation and codes of conduct for copyright collectives concluded:

Codes of conduct have little effect on improving the weak bargaining power of the majority of users – bargaining power is determined instead by the external regulatory regime in each jurisdiction, not by collecting societies per se.

From a Canadian perspective, the absence of measures is a significant impediment to ensuring full confidence in copyright administration and the consideration of new regulations should form part of the government’s efforts to reform the administration of copyright through the Board.

Thank you for your consideration.

How much did the poets think they should be getting? And the payment from the federal licence to publishers of scholarly materials (who usually own the copyright) does not mean nothing went to authors, who were paid separately.

beautiful.

never happen… like getting civians on police/secuirty boards,,,

but b nice thought.

The great Michael Geist still uses the Internet like an IBM Selectric, banging out ordinal numbers instead of using an ordered list and bravely, boldly, come-what-may deploying italics instead of

BLOCKQUOTE./and-his-slugs-are-still-a-joke-and-he-still-cant-understand-why-those-could-possibly-be-an-issue-i-mean-theyre-working-great-for-him-why-are-we-talking-about-this-whats-there-to-learn/.Michael Geist: The Internet “expert” the converged media and opentards all adore, and the “expert” with the weakest skills on the planet.

Pingback: This Week’s [in]Security – Issue 30 - Control Gap | Control Gap

Pingback: Access Copyright Calls for Massive Expansion of Damage Awards of Up To Ten Times Royalties - Michael Geist

Pingback: The Fight for Fair Copyright Returns: Canadian Government Launches Major Copyright Review - Michael Geist