Six years ago, then Public Safety Minister Vic Toews was challenged over his plans to introduce online surveillance legislation that experts feared would have significant harmful effects on privacy and the Internet. Mr. Toews infamously responded that critics “could either stand with us or with the child pornographers.” The bill and Mr. Toews’ comments sparked an immediate backlash, prompting the government to shelve the legislation less than two weeks after it was first introduced.

This week, telecom giant Bell led a coalition of companies and associations called FairPlay Canada in seeking support for a wide-ranging website blocking plan that could have similarly harmful effects on the Internet, representing a set-back for privacy, freedom of expression, and net neutrality. My Globe and Mail op-ed notes the coalition’s position echoes Mr. Toews, amounting to a challenge to the government and the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (the regulator that will consider the plan) that they can either stand with them or with the pirates.

While that need not be the choice – Canada’s Copyright Act already features some of the world’s toughest anti-piracy laws – the government and the CRTC should not hesitate to firmly reject the website blocking plan as a disproportionate, unconstitutional proposal sorely lacking in due process that is inconsistent with the current communications law framework.

The coalition, which also includes Rogers, Quebecor, and the CBC, has tried to paint the Canadian market as one rife with piracy, yet the data does not support its claims. For example, Music Canada recently reported that Canada is well below global averages in downloading music from unauthorized sites (33 per cent in Canada vs. 40 per cent globally) or stream ripping from sites such as YouTube (27 per cent in Canada vs. 35 per cent globally. Further, a 2017 report from the Canada Media Fund channeled the success of Netflix in noting that “some industry watchers have gone so far as to suggest that piracy has been ‘made pointless’ given the possibility of unlimited viewing in exchange for a single monthly price.”

Even if there was an urgent issue to address, the coalition’s proposal raises serious legal concerns. It envisions the creation of a new, not-for-profit organization that would be responsible for identifying sites to block. The block list would be submitted to the CRTC for approval, which would then order all Internet providers to use blocking technologies to stop access to the sites. The courts would remarkably be left out of the process with the potential for judicial review by the Federal Court of Appeal only coming after the block list was established and approved by the regulator.

The limitations of blocking technologies, which can often lead to over-blocking of lawful content, raises immediate red flags about whether site blocking would be consistent with the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. For example, when Telus restricted access to a pro-union website in 2005, it simultaneously blocked access to an additional 766 websites hosted by the same computer server. Given the implications for freedom of expression, an immediate legal challenge would be a certainty.

The absence of full judicial oversight and the likely Charter challenge are fatal flaws in the proposal, but they are by no means the only ones. The CRTC stated in 2016 in a case involving Quebec’s plan to block unlicensed online gambling sites that the law only permits blocking in “exceptional circumstances”, which places the onus on the coalition to demonstrate that the plan would further Canada’s telecommunications policy objectives. It does a poor job in this regard, relying on easily countered bromides that piracy “threatens the social and economic fabric of Canada”, that the telecommunications system should “encourage compliance with Canadian laws” and that website blocking “will significantly contribute toward the protection of the privacy of Canadian Internet users.”

The CRTC should be particularly wary of establishing a mandated blocking system given the likelihood that it will quickly expand beyond sites that “blatantly, overwhelmingly or structurally” engage in infringing or enabling or facilitating the infringing of copyright. For example, Bell, Rogers, and Quebecor last year targeted TVAddons, a site that contains considerable non-infringing content, that would presumably represent the type of site destined for the block list.

In fact, legitimate online video services could become another target. In 2015, Bell Media executives claimed that Canadians who used virtual private networks to access U.S. Netflix were stealing. The prospect of targeting VPN use, which has many legitimate uses, has long raised concerns for the privacy community, but the website blocking plan could emerge as an alternative with demands to block unlicensed foreign online video services. The U.S. was so concerned about the possibility of Canadian blocking that it demanded a provision prohibiting the practice be included in the Trans Pacific Partnership.

Much of the proposal ultimately rests on claims that website blocking has been implemented in other countries with positive market effects. Yet countries with site blocking such as the U.K., the Netherlands, Norway, Singapore, and Australia include more robust judicial review missing from this proposal. Moreover, the Canadian market is already outperforming many site blocking countries. For example, more Canadians per capita subscribe to Netflix than consumers in site blocking countries such as Italy or the U.K. and Canada recently surpassed Australia as the sixth largest music market in the world.

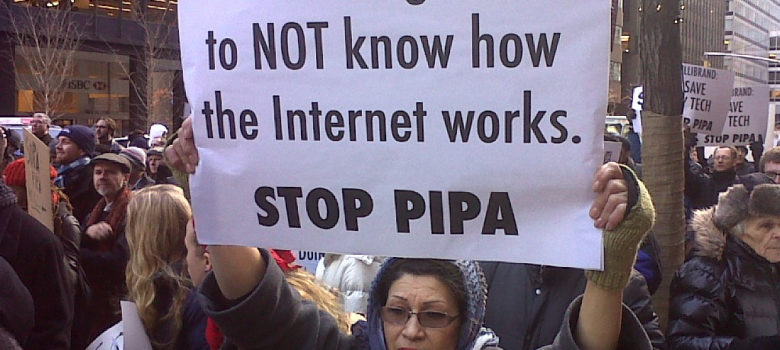

The U.S., which typically is viewed as the world’s most aggressive copyright enforcer, is notably missing from the list of site blocking countries. It considered the measure several years ago in controversial legislation known as the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), which generated massive online protests and was killed before the voting stage. The U.S. Congress has been wary of introducing similar legislation ever since, a useful lesson for the CRTC and the federal government, who would be well advised to swiftly dismiss the ill-advised and dangerous Canadian site blocking proposal.

Content creators should not be allowed to be ISPs due to the obvious, massive conflict of interest.

Perhaps Bell, Rogers et al need to be broken up into separate divisions or companies? That would instantly fix the problem of them lying and whining.

Once again, money gets to “speak”, regardless of the consequences.

Someone accused me of downloading an episode of “Game of Thrones”. I got tired of George R R Martin’s schtick of killing off characters back in the 1990s when I read stories such as “After The Festival”, and said exactly that in response.

A lot of the claims are simply made up. Prenda Law in the USA, ACS Law in the UK, and CEG TEK here in Canada.

Pingback: Canadian Internet Censorship Could Spark Charter Challenge - Geist

This is less about stopping Piracy, and more about Bell, the CBC, Cineplex, etc, watching the new generation of lean, fast, innovative companies taking larger and larger bites out of their pies – if they would stop trying to keep the status quo and do a bit of innovation on their own…. oh, but that’s not as easy as sitting back and doing nothing, trying to get the Feds to do your dirty work for you by making it easy to blacklist anything you don’t like as ‘Pirate’.

Have you ever seen a torrent site?

Stupid question. Of course you have. Then you know it has nothing to do with “fast, innovative companies”.

What kind of independent body would yank them off the Internet in favour of Bell. Come on, you have to do a lot better than that.

@George Bona Fide Software such as LibreOffice and Linux often has one or more torrent sites as one option for obtaining the software.

Was there a point you were trying to make?

I have never installed an internet file sharing application on any of my digital devices. I don’t even have standard home network file and printer sharing turned on between my windows, Apple and Linux PCs as a security precaution. I have seen a printer virus propagate at work. If I need to move something between them I use an Encrypted USB drive.

Apart from my personal ethics installing a file sharing app is one of the worst things you could do to compromise your device. I’ve seen that caution expressed in pretty much those words in IEEE journals.

https://www.us-cert.gov/ncas/tips/ST05-007

I remember dining with the Dean of Engineering at a local university during an IEEE Chapter meeting and talking about intellectual property rights and how to convey the concept that “this is stealing” to children and students.

https://www.ieee.org/about/ieee_code_of_conduct.pdf

5. e) “Not misusing or infringing the intellectual property of others”

Pingback: No Panic: Canadian TV and Film Production Posts Biggest Year Ever Raising Doubts About the Need for Site Blocking and Netflix Regulation - Michael Geist

Pingback: Privacy News Update, 2-18-18

This is CLEARLY a conflict of interest for these companies to sensor our internet content. We moch foreign countries who sensor their internet and we pride ourselves of being a free nation with freedom of speech. This would completely undermind that and remove our freedom of speech. This is absolutely NOT acceptable!!

Pingback: Tell the Canadian government to ignore Bell’s terrible idea to block websites | CENSORED.TODAY

Pingback: This Week’s [in]Security – Issue 45 - Control Gap | Control Gap