The Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology copyright review has focused exclusively on fair dealing and education to date, hearing from a broad spectrum of witnesses that education spending on licences has increased since 2012, that publisher profit margins have gone up during the same time period, and that distributions from the Access Copyright licence have declined. As discussed in yesterday’s post, the data points to the changing realities of access to materials with site licensing now constituting the majority of electronic reserves followed by open access or freely available online materials. Schools are also collectively spending millions of dollars on transactional licensing that grants access to specific works as needed. The role of fair dealing is relatively modest, reflecting a small part of overall access to materials.

The availability of alternative licences that offer better value than the Access Copyright licence lies at the heart of the decline in Access Copyright distributions. This was illustrated during an exchange at the Winnipeg hearing with Mary-Jo Romaniuk, the University Librarian at the University of Manitoba:

Mr. Dane Lloyd: You made an interesting comment, Ms. Andrew, about one of the reasons you are no longer with Access Copyright, as in the company, as Mr. Sheehan said, was because there was a lot of duplication and you were already paying for the rights of many things that access copyright was providing. Can you explain how that happens? How is there duplication? It seems to me that somebody pays for the right to sell a published work. How is somebody else also available to pay that? It seems like there is only one owner, or one licence holder, so how can you be accessing copyright protected materials by paying one person but not actually paying somebody who also holds the licence for that?

Ms. Mary-Jo Romaniuk: We’ll see how we answer this. I hope this answers your question. When we license material in the library, which is what she’s referring to, we pay a licence fee to the publisher, who again, we assume, divvies it out appropriately, so that is how we licence material. Once it’s licensed we have the right to use, and individuals use it. If we license five simultaneous users, five people can use it at the same time. If we license one, they take their turns. The fee for use is already paid in that fee. When we were paying access copyright, of course you pay by head count, so in essence we’ve already paid the fee for most of that licensed material and, as you can see, the amount of both our dollar value and kinds of licences have expanded greatly so the duplication would only be worse.

Mr. Dane Lloyd: Would you say that you’re paying for copyright? You’re just bypassing access copyright and paying the publishers directly?

Ms. Mary-Jo Romaniuk: That’s the model that’s there. Access Copyright is one mechanism. The other mechanism, of course, is for us to purchase material or licensed material from publishers, which we have always done.

Mr. Dane Lloyd: These publishers are publishing works that Access Copyright was also selling to you?

Ms. Mary-Jo Romaniuk: There can be multiple ways you can acquire a work or rights to use a work. Access Copyright is one.

Ms. Althea Wheeler: If I can add, I think part of the difference is if we’re looking at something that is born digital versus the print version, and we are increasingly purchasing those born digital versions of things. That’s I think where the difference comes between who is getting paid.

As Ms. Romaniuk rightly states, “there can be multiple ways you can acquire a work or rights to use a work. Access Copyright is one.” In fact, as noted yesterday, university data confirms that alternative licences are being used as the primary source for course e-reserves. For example, the University of Guelph told the committee:

Currently, 92% of the materials we acquire are digital, and the rights we negotiate provide for greater legal opportunities for the use of those materials. Students at the university access course readings in a variety of ways: they purchase textbooks from the university bookstore; they access materials placed on reserve in the learning management system, including 54% through direct links from licenced materials, 24% open and free Internet content, 6% via transactional licences, with the remaining 16% under fair dealing.

Not only are Access Copyright distributions declining, but the value of its licence is as well. This is due to at least two trends: (1) the availability of better value alternatives that cover the same material and (2) the declining size of the repertoire of materials that are likely to be copied. Note that these two trends are independent of the legal issue at the heart of the current committee discussion, namely whether fair dealing overlaps with the Access Copyright coverage for any remaining materials.

All sides agree that the Access Copyright licence would only apply in instances where education does not otherwise have the right to make a copy of the work. Even setting fair dealing to the side (it only represents roughly 16% of e-reserves content), education has acquired the right to use materials in the overwhelming majority of circumstances. The most important source is site licensing, which will be fully explored in tomorrow’s post. However, with more than half of all materials in e-reserves covered by alternative site licences that generate millions on revenues for aggregators, publishers and authors, any application of the Access Copyright licence in such circumstances would mean double payment for the same materials.

In addition to site licensing, the 24% of e-reserve materials that are open and free Internet content points to the continuing diminishing value of the Access Copyright licence in the years ahead. The role of open access licensing is particularly important, since the public has effectively already paid for many of the publications by funding research and researchers. Further, the continued growth of open access reflects a desire of the authors/researchers to ensure their work is widely disseminated. In many disciplines – the sciences, health, engineering, and law to name several – open access is increasingly the standard, meaning that Access Copyright’s demands for licence payments would require hundreds of thousands of students to pay for copying that does not exist.

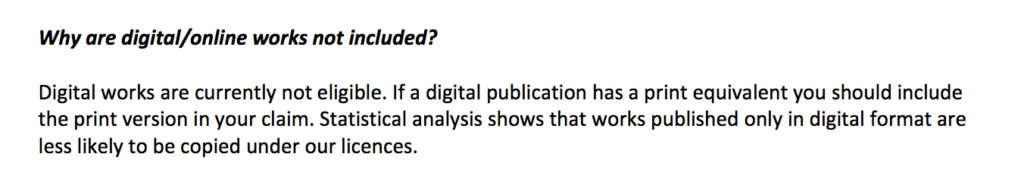

Yet the declining value of the Access Copyright licence is not solely a function of the availability of better value (or free) alternatives. Given copying trends identified by Access Copyright itself, its licence will continue to decline in value with each succeeding year. Access Copyright’s Payback system, which provides royalties to all writer affiliates, excludes all digital works. In terms of eligibility, its rules exclude “blogs, websites, e‐books, online articles and other similar publications. Only print editions can be claimed.”

Access Copyright Payback FAQ – Digital, http://www.accesscopyright.ca/media/115133/english_payback_faqs.pdf

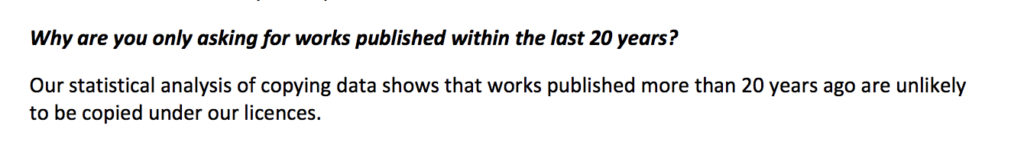

Given the growth of digital content, the Payback system will steadily become less reflective of the full scope of publishing and user access to materials. Moreover, the Payback system also excludes all works that are more than 20 years old on the grounds that they are rarely copied. According to the Access Copyright FAQ:

Access Copyright Payback FAQ – 20 years, http://www.accesscopyright.ca/media/115133/english_payback_faqs.pdf

Limiting the Access Copyright Payback system to print publications from the past 20 years means that the amount of materials being copied would be shrinking even if education wasn’t already licensing 60% of e-reserves. As more and more print content is licensed under open access or born digital, the size of the repertoire is surely getting smaller. These works falls outside of the system and are not compensated under Payback.

Moreover, the works of publishers and many creators also fall outside of the Payback system as Access Copyright’s own analysis finds that their works are unlikely to be copied. For well-established publishers with large back catalogues, this suggests their pre-1997 works are rarely copied. In order to fully monetize those older works in the digital environment, the publishers must primarily rely on site licences – the same site licenses Access Copyright downplays – to generate incremental revenues from educational institutions.

The same is true for authors. For example, Sylvia McNicoll, who appeared earlier before the committee, has been an accomplished author for decades, meaning that many of her books are now ineligible for Payback payments given that they are unlikely to be copied. The same is true for Margaret Atwood, one of Canada’s best known authors, who published the majority of her books, short fiction, and poetry before 1997. Indeed, alternative licensing is the real story of access within education today as the Access Copyright licence steadily diminishes in value in the digital environment. The full impact of site licensing will be explored in tomorrow’s post.

The Payback distribution has separate eligibility rules to the standard Access distribution. It isn’t therefore correct to say, for example, that the older Margaret Atwood novels are outside the main distribution scheme.

Pingback: Canadian Copyright, Fair Dealing and Education, Part Four: Fixing Fair Dealing for the Digital Age - Michael Geist

Pingback: Separating Fact From Fiction: The Reality of Canadian Copyright, Fair Dealing, and Education - Michael Geist