The review of Canadian copyright law continues this week with the Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology set to hear from Canadian ministers of education and the two leading copyright collectives, Access Copyright and Copibec. The committee review has now heard from dozens of witnesses, including a week-long cross-country tour. With the initial focus on copyright, education, and fair dealing, the MPs are grappling with three key trends since 2012: educational spending on licensing has increased, publisher profit margins has increased with increased sales of Canadian educational texts, and distributions from the Access Copyright licence have declined. This post, the first of four this week on copyright, fair dealing, and education, takes a closer look at the three trends and how they can be reconciled.

1. What Has Happened Since 2012?

i. Educational Spending on Licensing

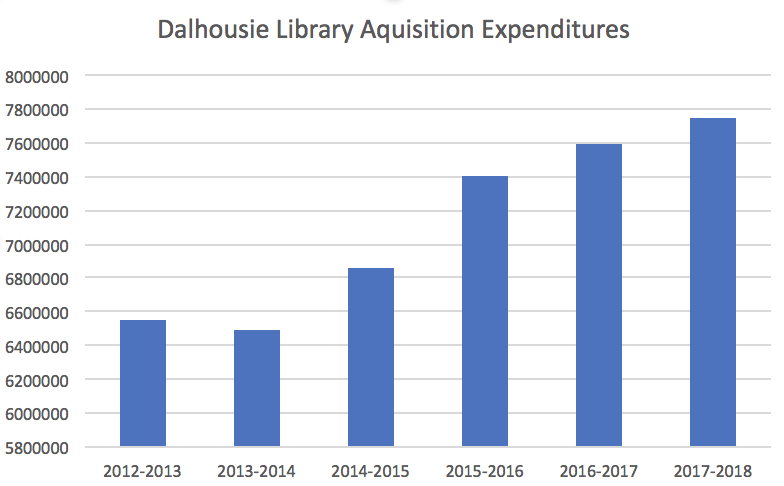

Contrary to the doom and gloom, data from several universities and Statistics Canada confirm that educational spending on licensing has increased since the last copyright reforms in 2012. For example, the spending at Dalhousie University since 2012 looks like this:

Dalhousie Library Expenditures, https://www.dal.ca/dept/financial-services/reports/budget-advisory-committee–bac–reports.html

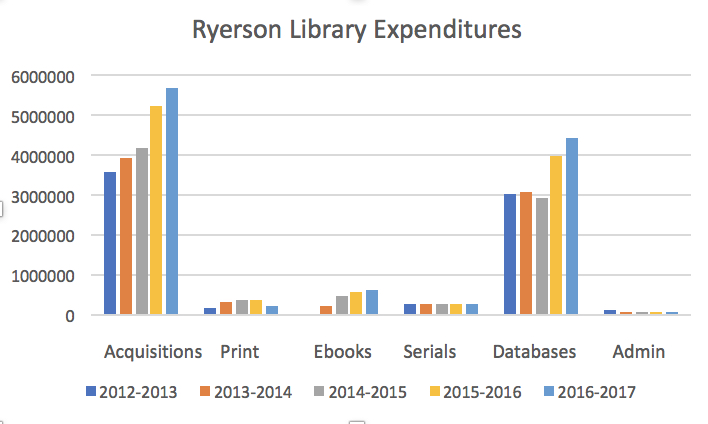

The spending at Ryerson shows a similar trend, with major investments in site licenses and e-books:

Ryerson Library Expenditures, Detailed, https://library.ryerson.ca/info/collections/budget/

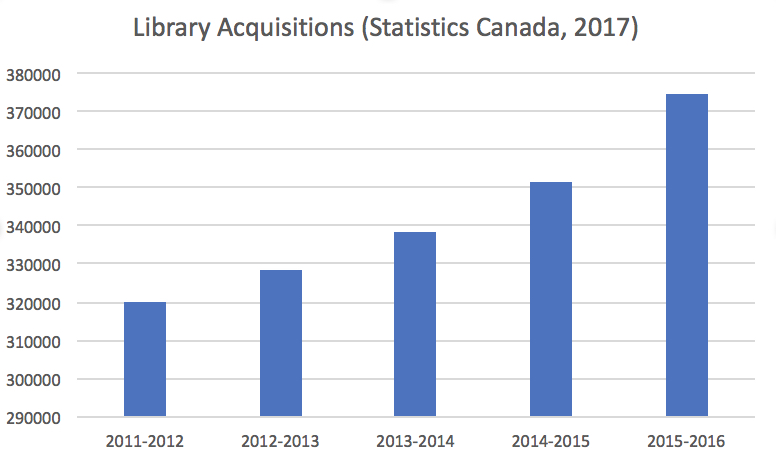

In fact, Statistics Canada, which surveys the Canadian Association of University Business Officers on university spending, shows the increased spending on content since the fair dealing decisions and reform is national in scope.

Statistics Canada Library Acquisitions, http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=3121

An upcoming post will more closely examine the hundreds of millions spent on licensing every year by the educational sector and what it means for accessing materials in schools.

ii. Canadian Publisher Revenues

The Canadian publisher data from Statistics Canada that shows the Canadian publishing market largely unaffected by fair dealing given the other changes taking place in the market. The data released in late March of this year shows that Canadian publisher operating profit margin has increased since the copyright reforms in 2012 as it stood at 9.4% in 2012, 9.6% in 2014, and 10.2% in 2016.

As for the education publishing market, the Statscan data shows sales increasing for educational titles from Canadian publishers: $376.6 million in 2014 to $395.1 million in 2016. The data shows similar increases for children’s books from Canadian publishers. Interestingly, there is a parallel decline for educational sales as agents, suggesting that the educational market overall has seen little change other than a shift toward Canadian titles. The success of Canadian authors is mirrored by the Statscan data on nationality of sales with Canadian authors seeing a significant increase in sales in Canada, whereas foreign authors have experienced a slight decline. In considering new titles published, there is a slight decline among Canadian authors of about 6%, but the rate of decline is far higher – nearly 13% – for foreign authors.

The Canadian publisher trends mirror those found with publishers around the world. For example, Cambridge University Press reports higher operating profits with digital products now constituting 36% of revenues. Yet its latest annual report notes the changes in the academic market worldwide:

The Higher Education market is going though rapid change and challenges, including the rise of open educational resources, disruptive technologies and shifts in purchasing habits, which have hit particularly hard at the entry level undergraduate market.

Oxford University Press tells a similar story in its most recent annual report, with many challenges that have little to do with fair dealing or collective licensing:

This year market conditions continued to challenge academic and research publishers. Libraries continue to make evidence-based purchasing decisions, with their budgets growing very slowly. Higher Education (HE) rental models are growing in popularity, and there is an increasing demand from funders for Open Access or Open Educational Resources. Online piracy remains a significant threat in the academic market, and publishers continue to invest heavily in digital offerings to meet evolving user expectations. Despite these factors, the Press’s academic publishing achieved a solid turnover increase, with the academic book business returning to growth.

iii. Access Copyright Distribution Decline

Given the shift away from the Access Copyright toward other licenses and methods of acquisition, the distributions from the copyright collective have unsurprisingly declined. Access Copyright’s latest annual report points to sharp drops in revenues from education and corresponding declines in distributions to creators and publishers.

The impact of the declines in distributions have been discussed by several witnesses and briefs. Broadview Press, which used its submission to the committee to urge it to retain the current copyright term of life of the author of plus 50 years (ie. do not harm the public domain), says that it generates approximately $3.5 million annually in sales. Its revenue from Access Copyright has dropped by $30,000 (from $50,000 to $20,000), or just under 1% of total revenues. The impact on House of Anansi is even smaller. Its submission reports its annual revenue is approximately $7 million with Access Copyright revenues dropping by about $17,000 (from $22,000 to $5,500) or 0.2%.

Authors have also pointed to the decline in Access Copyright royalties. For example, author Sylvia McNicoll, presenting for the Canadian Society of Children’s Authors, Illustrators and Performers, submitted a brief indicating that in 2012, she earned $46,000 with the Access Copyright royalty contributing $2,578.68. Last year, her income dropped to $12,000 and the Access Copyright royalty declined to $400. The decline of $2,100 in Access Copyright royalties is significant, though obviously there are other factors at play since she reports that her overall income dropped by $34,000.

2. Reconciling the Data

The three trends have left MPs searching for answers about how spending is on the rise but Access Copyright distributions have declined. For authors groups, the answer is simple: they argue fair dealing is responsible for the education decision to shift away from the Access Copyright licence. They point to aggregate photocopying data from several years ago to suggest that there is still considerable copying taking place and that it is unfairly uncompensated.

Yet the data suggests that fair dealing is a very small part of the story. First, copying itself is a shrinking method of accessing materials. Access Copyright often talks about 600 million copied pages, but the Federal Court of Appeal has noted in a case involving K-12 schools that that number was actually less than 10 pages per student per month, suggesting that even in aggregate the amount of copying was not unfair:

In explaining why looking at the aggregate volume of copies was not helpful to its assessment of whether the copies were widely distributed, the Board reasonably applied the Supreme Court’s teachings in CCH and Alberta. I find no reviewable error on the part of the Board in this respect. In fact, this finding is reasonable even if one were to consider that the overall number of copies represents approximately 90 pages per student per year. I agree with the Consortium that this figure does not support the view that this factor could only tend to a conclusion that the dealing was not fair.

Moreover, the time of providing photocopied pages of materials to students is rapidly coming to an end. As Allan Bell, Associate University Librarian at UBC noted to the committee:

Our students are demanding more digital content, and more digital experiences. Selling photocopies to 19 year olds is something that does not work today, and certainly won’t work tomorrow.

In fact, Bell advised that books are increasingly being placed in storage and not copied at all:

The other thing is the circulation. Our books are being used less. Indeed, many of our books are being put into a storage facility, where they are safely not being copied.

Canadian universities have given the committee precise data on the sources for course materials found in learning management systems on reserve. The University of Guelph told the committee:

Currently, 92% of the materials we acquire are digital, and the rights we negotiate provide for

greater legal opportunities for the use of those materials. Students at the university access course readings in a variety of ways: they purchase textbooks from the university bookstore; they access materials placed on reserve in the learning management system, including 54% through direct

links from licenced materials, 24% open and free Internet content, 6% via transactional licences, with the remaining 16% under fair dealing.

Ryerson provided similar figures to the committee:

Through Ryerson’s copyright management e-reserve system and other commission services we spend more than $150,000 annually in transactional commissions for copies that are not within our licensed resources or are beyond fair dealing. Some of these transactional licences are direct publisher transactions or brokered through the U.S. copyright clearance centre and fees are returned to Access Copyright as Access Copyright does not currently permit direct transactional commissions, as far as Ryerson knows. More than 80% to 90% of the content we make over to our students in e-reserve is covered through licences for digital materials, links to legally posted publicly available materials and open access content.

The data points to the changing realities of access to materials with site licensing now constituting the majority of electronic reserves followed by open access or freely available online materials. Schools are also collectively spending millions of dollars on transactional licensing that grants access to specific works as needed. The fact that universities spend significant sums on transactional licenses also reinforces that no one thinks that fair dealing is a free-for-all. The role of fair dealing is relatively modest, reflecting a small part of overall availability of works.

For MPs seeking answers to the state of educational copying in Canada, the data tells us that schools continue to spend and publishers continue to garner growing revenues. The emergence of licensing alternatives to Access Copyright is the obvious reason for declining distributions at that collective, not fair dealing. Posts later this week will continue the focus on the declining value of the Access Copyright licence as education identifies more convenient and flexible alternatives.

Sylvia McNicoll said that the reason her total income declined is that students now copy her work rather than buy it, so she is hit both my a drop in her Access Copyright income AND from book royalties. And Broadview and House of Anansi explained that the proper comparison when quantifying their reduced AC income is not against revenue, but profit, of which it represents a far higher proportion.

As a former youth librarian, I don’t think the problem is students copying her work. She’s a fiction writer. I haven’t ever seen a student (or teacher) copy a novel before. The problem is that students have stopped reading for pleasure and have stopped purchasing books. Sylvia only has three books on Goodreads with over 100 ratings (let alone reviews) and only one above 112. The problem is not due to Fair Dealing, but children’s increasing lack of interest in reading. With more emphasis on standardized testing, teachers don’t have time to give free reading or book report assignments anymore. And students are more apt to play video games and watch Netflix nowadays. They don’t even watch television anymore, because they hate commercials.

Pingback: Canadian Copyright, Fair Dealing and Education, Part Two: The Declining Value of the Access Copyright Licence - Michael Geist

so if copyright acquisition costs have gone up HAS the “return on investment” gone up? IE are the schools getting better resources OR are they chasing a system increasingly failing their needs?

and if so THEN the system NEEDS “fixing” as education and the quality / cost is a BIG social issue that at this point Canada leads the USA on

Pingback: Canadian Copyright, Fair Dealing and Education, Part Three: Exploring the Impact of Site Licensing at Canadian Universities - Michael Geist

Pingback: Canadian Copyright, Fair Dealing and Education, Part Four: Fixing Fair Dealing for the Digital Age - Michael Geist

Thank you for all of the hard work you have put into your series. It has been elucidating.

Pingback: Separating Fact From Fiction: The Reality of Canadian Copyright, Fair Dealing, and Education - Michael Geist

Pingback: Authors Alliance, Teachers, and Copyright Experts Support Limitations and Exceptions for Education at WIPO SCCR/36 | Authors Alliance