This series on misleading on fair dealing has placed the spotlight on the changing state of educational copying including the significant decline in book copying as part of coursepack materials and the gradual abandonment of print coursepacks in favour of digital course management systems (CMS). Other posts in the series examined the legal effect of the 2012 reforms and the wildly exaggerated suggestion of 600 million uncompensated copies each year.

This post highlights the massive education investment in e-book licensing. The shift to e-book licensing has significant implications for the fair dealing debate since it confirms that the decline of the Access Copyright licence is not the result of institutions seeking free access, but rather the gravitation toward alternative licences that offer better value for teachers, students, and the taxpayer.

Given Access Copyright’s reliance on conventional print coursepacks and book copying, it is unsurprising that CEO Roanie Levy tried to convince the copyright review that there are “two buckets” of content: journals and books. Levy argued that educational institutions license journals, but not books:

We don’t dispute that the university sectors may in fact be paying more and more for content. What’s important to keep in mind is that the content that they are licensing and paying through their library licences is different from the content that they are copying under their copying policies. We’re talking about two different buckets of content. There is some overlap, but very little overlap.

The content that they are licensing is, through their own testimonies before you, mainly journal articles. As an example, CRKN testified that out of $125 million, $122 million is spent with foreign publishers. That content is created often by academics, people who rely on a salary in order to be compensated for their contributions. The content that is copied historically under the Access Copyright licence, today under their fair dealing guidelines, is mostly books, not journals.

During the same appearance, Levy characterized the difference as research materials as opposed to instructional materials:

The material that tends to get copied and used in class for instruction is different from the material that is used for research. That’s where you get the science, technical, and medical journal publishers. The five big multinational publishers are in that category. The licences that they have through CRKN are for the STM, science, technical, and medical journals. What gets copied and no longer paid for is the educational content, the trade content, the stuff that is used for instructional purposes.

The goal of this argument is clear: to convince the committee that the increased spending on licensing by educational institutions does not address the content covered by the Access Copyright licence. Yet aside from the fact that the data indicates there is far less copying of books and that print coursepacks (which are more likely to include book excerpts) are rapidly being replaced by digital course management systems (CMS), the data also leaves no doubt that Levy is wrong about book licensing. Canadian educational institutions are investing heavily in e-book licenses. Indeed, in recent years many institutions have adopted “digital first” policies in which they purchase digital copies of books rather than the physical ones. In doing so, educational institutions typically purchase both access to the work and a licence for multiple uses and/or inclusion in a CMS. This means that the e-book licence replaces the Access Copyright licence, compensating publishers and authors while providing students and teachers with greater flexibility and value. Moreover, many of the licences are perpetual, meaning that rights holders are paid a higher upfront fee in return for no subsequent royalties or payments.

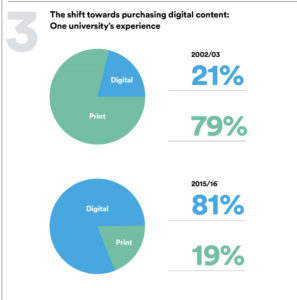

The copyright review has repeatedly been provided with evidence of the shift to digital licensing and the significant investment in e-books. Universities Canada demonstrated the shift with this chart on one university’s experience:

Universities Canada, The Changing Landscape of Canadian Copyright and Universities, https://www.univcan.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/copyright-parliamentary-review-submission-june-2018.pdf

Universities big and small have pointed to increased spending on electronic books. Trent University submitted to the committee:

The trend at Trent away from print on paper to digital is clearly evident from the spending on acquisitions between 2014/15 and 2016/17. During that period spending on print monographs went from $30,102 to $5722, a decline of 80%, whereas spending on ebooks went from $43,901 to $97,985, an increase of 46%, over the same period.

MacEwan University provided the committee with data showing a similar trend:

MacEwan library expended $2.6 million on acquisitions in 2017-2018 – a 98% increase since the 2009-2010 academic year. Digital content such as journals, eBooks, and streaming audio and video currently represents around 80% of the library collections budget.

The University of Calgary reported to the committee:

A growing proportion of library spending at UCalgary is on digital resources. The library has a buy-digital acquisition policy, unless a print resource is explicitly requested or electronic version is unavailable. In 2017/18, the university spent $9.8 million on digital resources, or 90.8 per cent of its acquisition spending.

It also highlighted the value of e-book licensing, explaining why the licence provides better value than transactional licensing or print copying:

eBook licenses for use in a course are often a more cost-effective approach for the university. A license for a multi-user eBook can cost less than a transactional license, and access is not limited only to students enrolled in one course. For example:

- A transactional license for two chapters of Oil: a Beginner’s Guide (2008) by Vaclav Smil for a class of 410 students would cost the library $2,463 USD. An unlimited license for the eBook version is $29.90 USD, and the book would be available to all library users.

- A transactional license for two chapters from the print book version of Negotiating a Vacant Lot: Studying the Visual in Canada (2014) by Lynda Jessop et al. for a class of 60 students is $414 CAD, while an unlimited license for the eBook version is $150 USD.

The University of Alberta’s open data project provides remarkable detail on all subscriptions and purchases by the university library. The data sets show year-by-year, work-by-work pricing, demonstrating that even a single university can spend hundreds of thousands of dollars annually to acquire access to works, many in perpetuity (thanks to University of Alberta’s Trish Chatterley for the assistance). The dataset shows massive investments in e-books from publishers around the world. For example, last year, it spent over $500,000 for the Springer e-book archive, which provides perpetual access to 110,000 books with the ability to use full chapters for course materials.

With regard to the Canadian publisher e-book licensing, the data discussed below suggests that the expenditures and range of Canadian materials is significant. For example, one of the largest Canadian e-book databases comes from the Canadian Electronic Library with a database known as DesLibris. It features thousands of Canadian e-books from Canadian publishers. Last year, the University of Alberta alone spent $24,000 on a licence to access to the database.

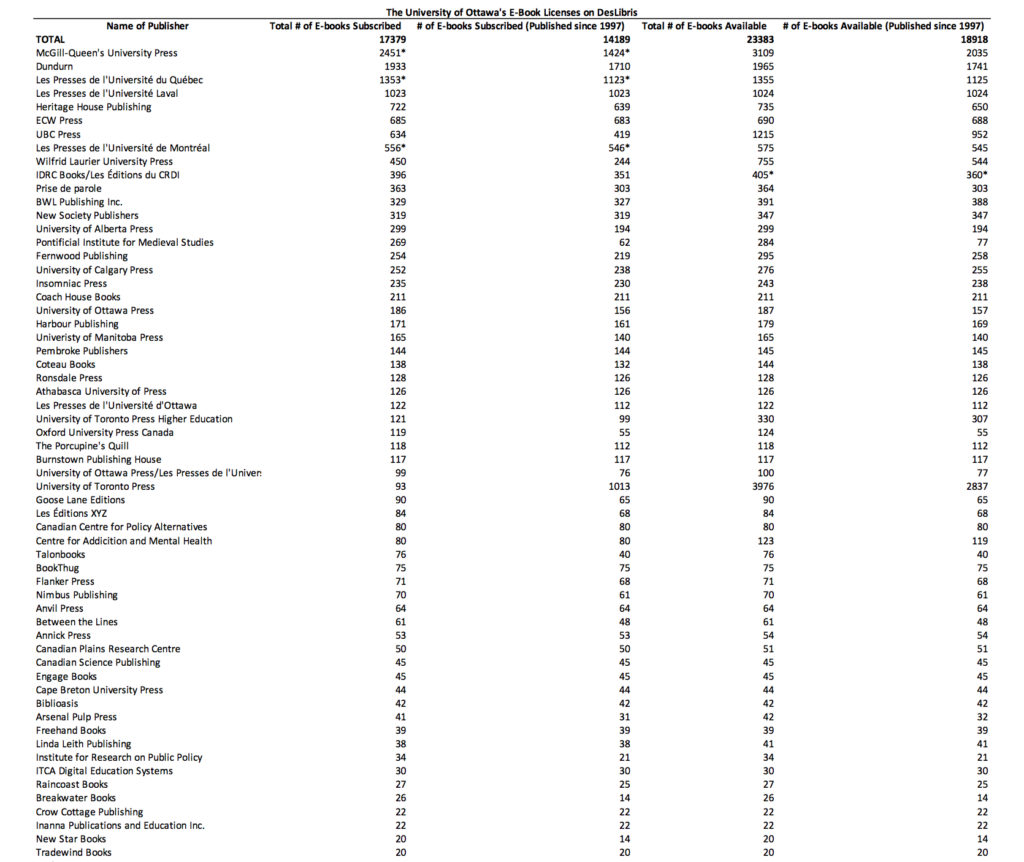

While it is challenging to identify precisely what is covered under the licence at each institution, the University of Ottawa also has a licence to the database. At the University of Ottawa, there are now nearly 1.4 million e-books under licence. Working with University of Ottawa student Tamara Mascisch-Cohen, we tried to identify the scope of the university’s e-book licences for Canadian publishers within DesLibris (which is just one of several Canadian e-book databases licensed at the university). The University of Ottawa is particularly interesting in this regard since it licences both English and French books from dozens of Canadian publishers (thanks to librarians Tony Horava and Sarah Hill for the assistance).

We looked specifically for four metrics by publisher: number of licensed e-books, number of licensed e-books published since 1997, total number of e-books available, and total number of e-books published since 1997 available. The metrics were designed to provide a sense of licensed e-books from a single database along with a better understanding of how many e-books fell within the last 20 years (Access Copyright says books older than 20 years are rarely copied and are ineligible for its Payback system) and whether the university was purchasing access to the majority of e-books available for subscription. Data on the top 60 Canadian presses is posted below:

University of Ottawa DesLibris data

The data shows a huge investment in Canadian e-books with universities licensing access to thousands of them across dozens of Canadian publishers. In fact, the University of Ottawa approach suggests that universities will typically licence the majority of e-books that are made available by Canadian publishers. In other words, the only thing stopping more e-book licensing are publishers who fail to include them within their databases. Further, there are a sizable number of e-books that are licensed that were published before 1997. These e-books are typically not copied (according to data from Access Copyright) and would not return royalties from the Payback system for the authors or publishers, meaning that site licensing is a crucial way to obtain an ongoing economic return from these older titles.

Moreover, this is only one database. The University of Ottawa library advises that it has purchased perpetual access to more than 15,000 books from Canadian publishers, including thousands of books from the largest publishers such as University of Toronto Press, McGill-Queen’s University Press, and UBC Press as well as dozens of smaller presses that have also sold perpetual access.

For example, the University of Ottawa has licensed access to over 98 per cent of the Dundurn Press e-books that are available through DesLibris: 1,933 Dundurn Press e-books of a total of 1,965 available e-books through the database. Dundurn has also sold 459 e-books under perpetual licences to the university. There is similar data for other Canadian publishers. ECW Press, whose site says it has published “close to 1,000 books” told the industry committee earlier this year that it has lost significant educational adoption revenues. Yet the University of Ottawa has licensed over 99 per cent of the available ECW e-books from DesLibris: 685 out of a total 690. ECW has also sold 339 e-books – about a third of its entire catalogue – under perpetual licences to the university.

Fernwood Publishing, a Canadian publisher that started in Halifax and expanded to Winnipeg, was also discussed at the copyright review. It says it has published over 450 titles over the past 20 years. The University of Ottawa has licensed 86 per cent of the available Fernwood e-book on DesLibris: 254 out of a total of 295. Fernwood has also sold 186 e-books under perpetual licences to the university. The data is replicated at many Canadian publishers, who criticize fair dealing yet remain silent on the new revenues from site licensing their e-books and on the fact that those licences typically mean that potential copying of their works is paid copying, not copying based on fair dealing.

The data is unequivocal. Claims that universities do not licence books is simply false. Rather, there has been a dramatic shift toward e-book licensing, with those licences (many of which are perpetual) effectively replacing the Access Copyright licence, compensating publishers and authors, and providing students and teachers with greater flexibility and value.

Mr. Geist continues to conflate library acquisition budgets with licensing agreements that allow libraries to reproduce a certain amount of what they have already purchased.

Regarding the accuracy of the numbers cited by Access Copyright in terms of the amount of copying taking place, the universities and schools have the numbers. They say they are in compliance, but the only objective look (Judge Phelan in York v Access ) Copyright) found that 30% of the copying at York fell outside their own guidelines (which were also judged to be unfair). If universities and schools have nothing to hide and are truly in compliance, open the books and let an independent adjudicator decide.

“In respect of LMSs, Access and York agreed to design and implement a study of the copying of published work by staff on LMSs. The result was that 16.3 million digital exposures

relevant to fair dealing were posted on York’s LMSs between September 2011 and December2013. Generally, 70% of the volume of copying on LMS systems fell within the quantitative

limits of York’s Guidelines” (from Judge Phelan’s decision)

I think it’s increasingly obvious from the number of posts Mr. Geist has recently made around fair dealing (and and the exaggerated claims made in them) that it’s time up for him and his ilk. The writing is on the wall, no? First a Federal Court slams York U. (and by extension every other Canadian University that has implemented similar copying guidelines) for unfair dealing. Last week Universite Laval signed a licensing agreement with Copibec retroactive to 2014, which is precisely what York U, English universities generally, and K-12 boards will be doing over the next few years.

Pingback: Misleading on Fair Dealing, Part 6: Why Site Licences Offer Education More than the Access Copyright Licence - Michael Geist

Pingback: An Open Letter to MP Randy Boissonault | Fair Duty

Pingback: Misleading on Fair Dealing, Part 10: Rejecting Access Copyright's Demand to Force Its Licence on Canadian Education - Michael Geist

Pingback: excerpts | Fair Duty

Pingback: Copyright and Culture: My Submission to the Canadian Heritage Committee Study on Remuneration Models for Artists and Creative Industries - Michael Geist