My series on why the Industry committee was right to ignore the Canadian Heritage committee study as part of the national copyright review has previously discussed process (the government vested sole responsibility with the Industry committee), an examination of the witness and brief list that confirms that Industry conducted a much more comprehensive consultation that overlapped with much of Heritage but also included hundreds of additional witnesses and briefs, and the (im)balance among witnesses which indicates that the Industry committee made a greater effort to hear a wide range of perspectives consistent with the diverse views on copyright.

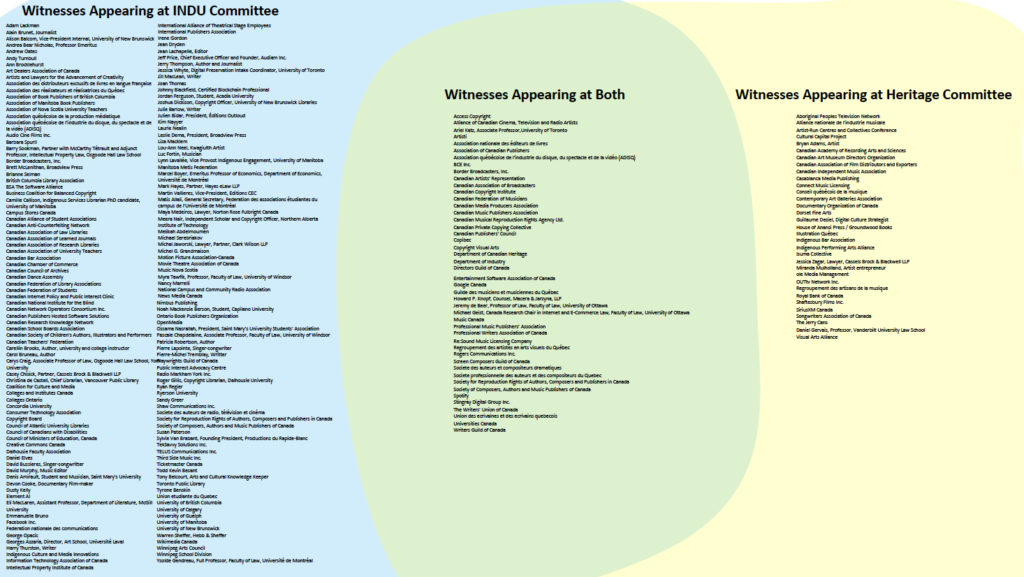

The data from the previous posts left little doubt that the Industry committee copyright review conducted a far more comprehensive consultation with two and a half times as many witnesses as the Heritage committee: 203 organizations and individuals for INDU vs. 79 for Canadian Heritage. INDU also ensured greater geographic representation, having held lengthy hearings in Halifax, Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg, and Vancouver.

Comparison of INDU vs. CHPC copyright witnesses

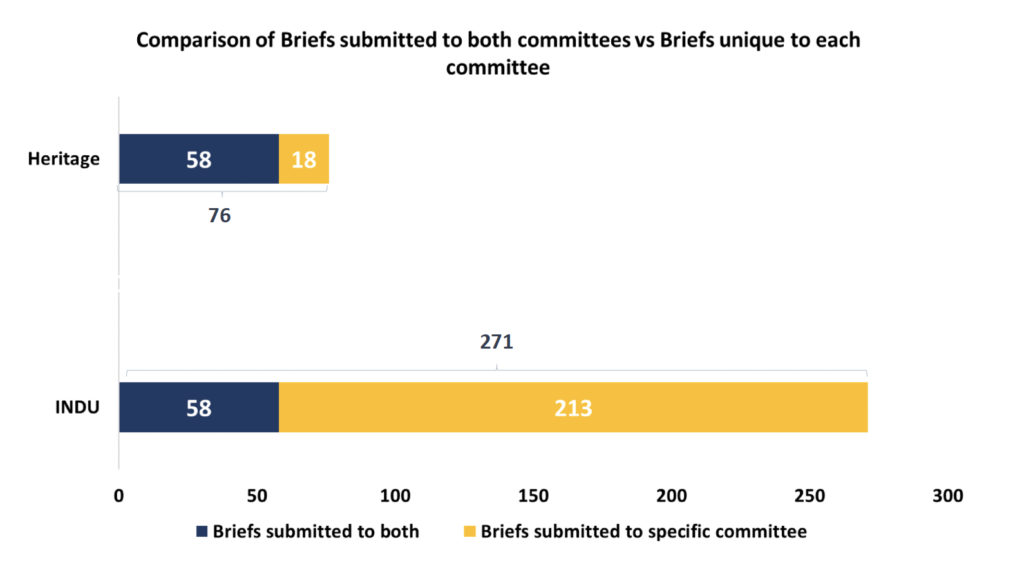

The submission of briefs tell a similar story. Both committees invited the public to submit briefs if they were unable to appear as witnesses or to supplement their testimony. INDU also received far more briefs: 271 briefs went to INDU vs. just 76 to Heritage.

Brief comparison

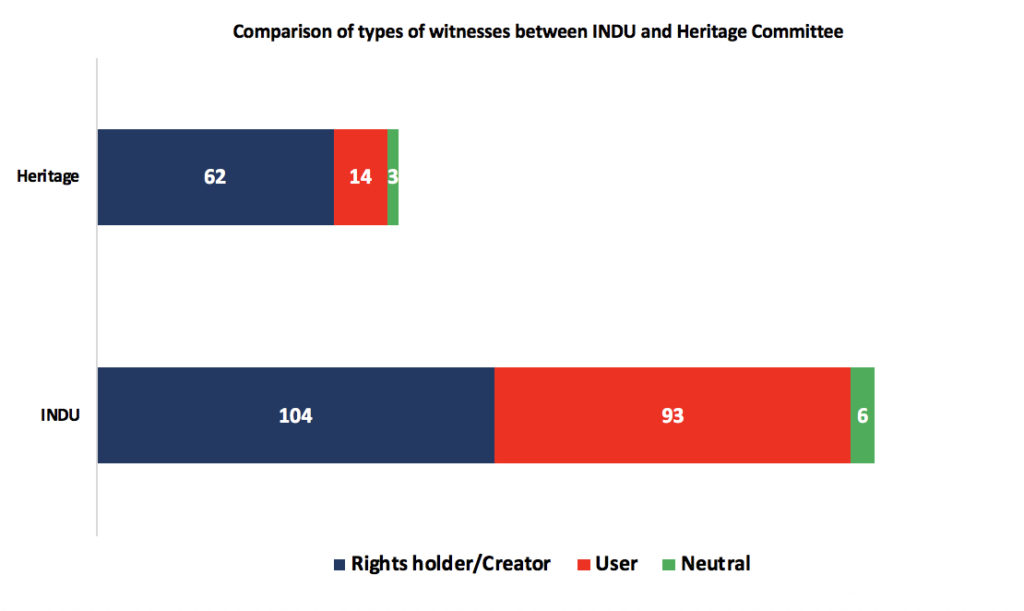

Not only was the INDU copyright review more extensive, it was also far more inclusive and balanced. The data shows that the Industry committee heard from more rights holders and creators than user groups, but was still relatively balanced: 52% of witnesses presented rights holder or creator perspectives, 45% presented user perspectives, and 3% neutral witnesses. In fact, the Industry committee heard from more witnesses representing rights holders and creators than all Heritage witnesses combined. By contrast, 80% of the witnesses before Heritage were rights holder and creator perspectives with only 16% – 14 witnesses – representing a user perspective.

Witness comparison by type – INDU vs. CHPC

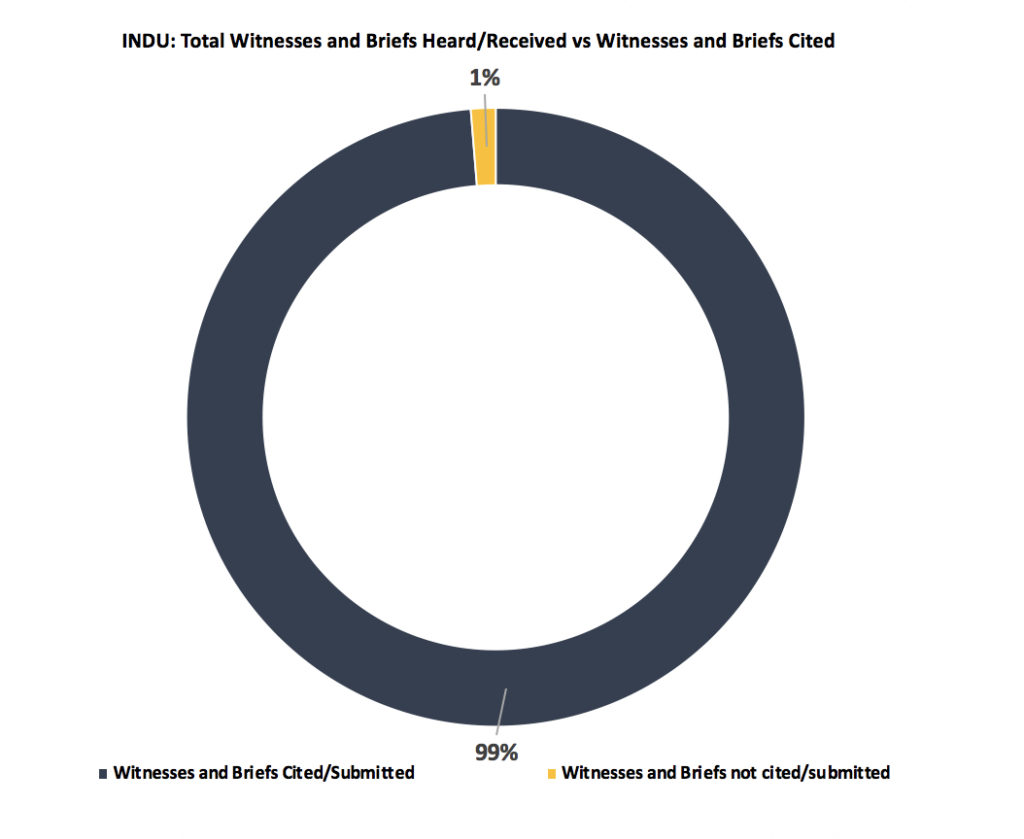

Yet participation alone does not tell the whole story. Just as important – perhaps even more important – is whether the witnesses and briefs were fully considered by the committees. Given that all drafting deliberations occur behind closed doors, the best proxy for consideration is citation by the committee. A committee may disagree with a witness or a submission, but citation in the final report sends the message that the perspective was at least considered. For the purposes of this analysis, where an individual or group appeared as a witness and submitted a brief, citing to either submission is treated as citation (in other words, not citing a witness appearance still counts as a citation if their brief is cited and vice versa).

The INDU citation data is remarkable: after hearing from nearly 400 organizations and individuals via witnesses and briefs, the committee report cited 99% of them (383 of the 388 individuals and groups who appeared as witnesses and/or submitted a brief).

INDU Citations

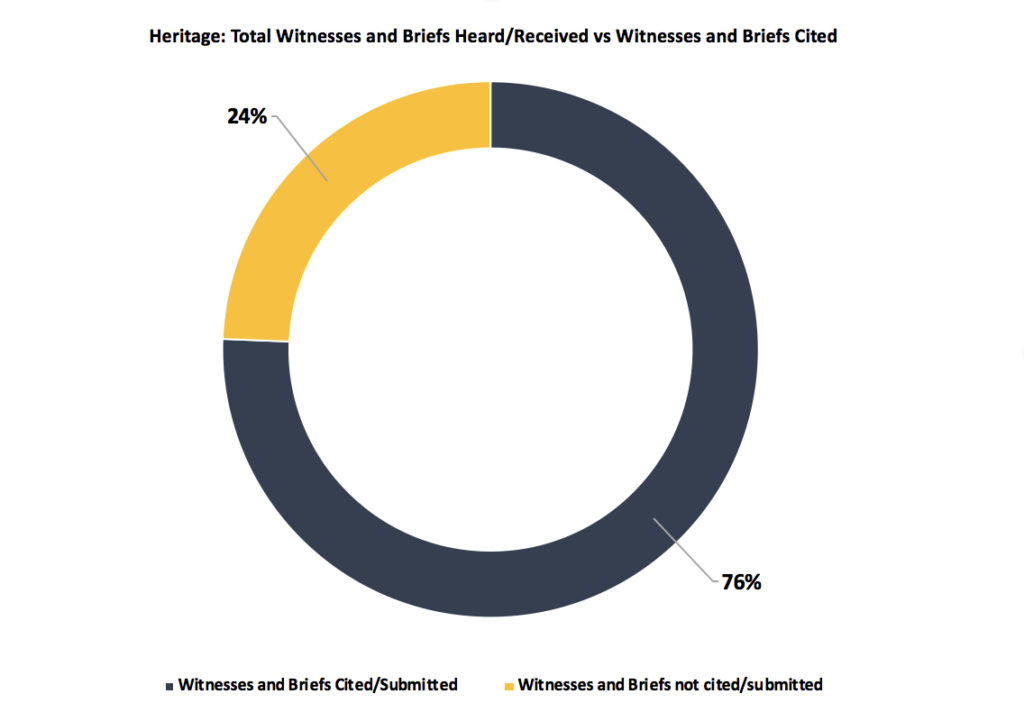

By comparison, Heritage had less than one-third the number of unique witnesses and briefs – only 119 – but failed to cite 24% of them. With roughly one of every four witnesses or submissions left uncited, Heritage sent the message that many of witnesses and submissions were left unconsidered.

Heritage – copyright cited

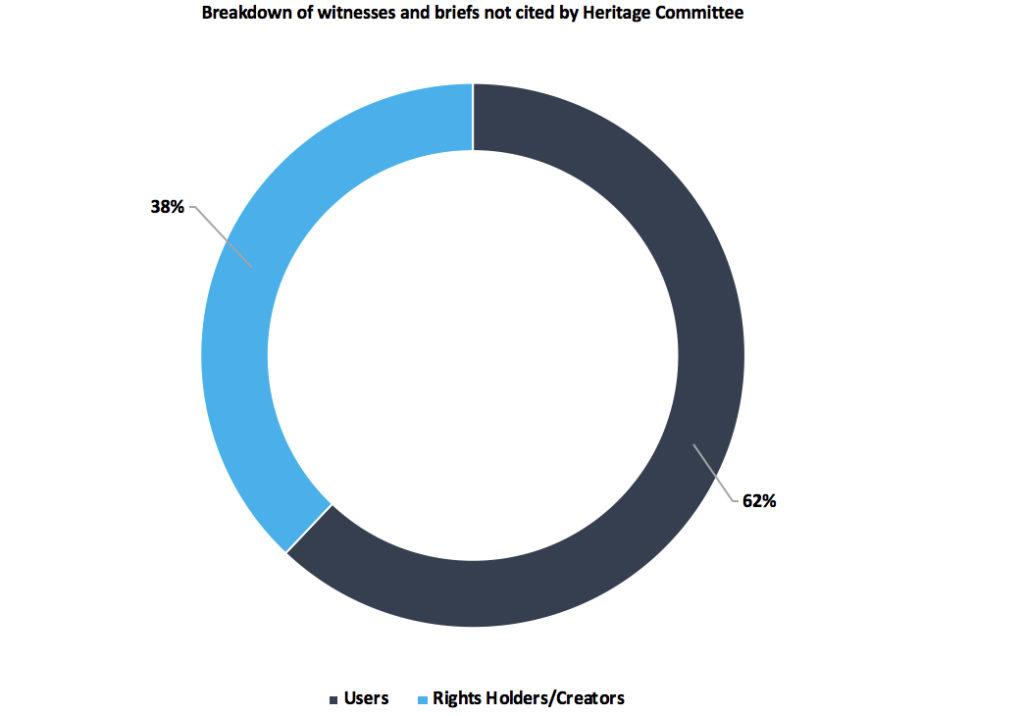

Moreover, the uncited 24% was not evenly balanced. An assessment of the uncited submissions and witnesses reveals that 62% provided user perspectives. In other words, not only did the committee limit the number of user-focused witnesses to only 16%, but when it did hear user perspectives, those views were more likely not to be cited by the committee.

Canadian Heritage – not cited

Much like the imbalance in witnesses, Heritage supporters may argue that the citation data similarly reflects a committee focused on rights holders and creators. That may be so, but it undermines confidence in a consultation process in which all stakeholders are invited to provide their perspective, but user oriented perspectives are more likely to be ignored. Further, when contrasted with INDU’s commitment to citing virtually all participants, it provides a stark comparison between inclusive policy development driven by evidence and a narrow exercise that reflected limited views. When a future government looks for a roadmap to determine new copyright policies, there is little doubt to which study they should turn.